In this blog, writer and publisher Màiri Kidd looks at how the translation of literature between languages – large and small – can give us other windows on the world.

I was once told, I’m pretty sure – and if it’s not true, I don’t care, because it would be great if it were true – that in the early days of the Irish Republic they conducted a massive translation project. A committee or panel, or perhaps just one person, would make a selection of the best books and writers in the world, and they would then translate them into Irish. That gave the Irish two things.

First, they soon had a load of books. It took Tolstoy six years to write War & Peace; but it would maybe only take about two years to translate. And there are 600,000 words in War & Peace, most books are (a lot!) shorter than that.

The second thing the Irish ended up with was a bunch of translators who had spent time studying amazing books from different parts of the world. And some of these translators were also writers. What an opportunity for a writer! What a training!

Why, then, am I looking back a hundred years when this series of blogs looks forward to 2045? Well, the basic job of translating is as detailed and challenging as ever, but most other things in that world are a lot easier than they used to be. Once upon a time, translators worked on paper and then had to go back and forth for editing, typesetting and so on. Today files whizz back and forth in a second, there are dictionaries that give us a response in the same time it takes to heave a large printed dictionary off the shelf, and there companies from all over the world are used to working together. Some books, especially illustrated books such as children’s books, are printed in many languages at the same time. Only the text files are modified.

BUT while all this opens doors, does it really help minority languages? Probably, in a way, because it’s cheaper to take part in a large-scale print job involving lots of different languages, and the cheaper books can be produced, the more we can publish of them. But these books usually originate in the major languages of the world. As such, they represent the major cultures of the world. That’s fine, to an extent – we know, for example, that children enjoy meeting old pals such as the Gruffalo in Gaelic as well as English. But if books are windows on the world, showing us different places, different people, different things that we were not aware of before, wouldn’t we want access to the small cultures too?

One year, more books came out, per head of population, in the Faroe Islands than anywhere else in the world. But you need to have Faroese to read them, however, as there is little, if any, translation available. Who knows which books appeared in Welsh, or in Sami, or in Cree, or in other minority languages? What if we could read them in Gaelic?

It’s not that we don’t have any access to books from other minority languages though. Years ago Little Stobag came to us from Wales – do you remember her, the cheeky wee witch and her friends? Some books have also gone back and forth between Scotland and Ireland. But not many came to us from further afield. You can understand why they came from the countries closest to us; we had people who spoke both Gaelic and Irish, or Gaelic and Welsh. Perhaps not as many understand Gaelic and Cree.

Companies across Scotland are trying to open windows on various places through English language books. Sandstone Press won the 2019 Man Booker International award for Celestial Bodies by Omanian Jokha Alharthi. Vagabond Voices has a list of beautiful books from many languages. Charco Press publishes books from South American countries where Spanish and related languages are spoken. (‘Charco’ means pond, but it also has another meaning, the Atlantic. “Cruzar e charco,” is a bit like someone in the United States saying, “cross the pond.” That’s a wee window on another language for you.)

I wonder, then, if there is a way to build on what is already happening with books originally written in minority languages? If books are ‘windows’, then in the translation business we talk about ‘bridges’, that is, a common language that people from different cultures speak. If we met someone with Cree, for example, we might speak French, or English. Those Irish people back in the day often worked with English as a bridge. Might there be collaborations that would allow us to publish a book in Gaelic AND English – or Scots? – simultaneously?

In 2045, I hope that we will have the opportunity to look through windows large and small so that we can understand both the differences between us, and the great things that we have in common. In the case of minority languages, for me at least, more unites us than divides. A way of looking at the world, knowledge passed down through the ages, a wealth of songs and poetry. We often talk about diversity. Aren’t our languages a bit like that, too, and shouldn’t they be widely shared?

Màiri Kidd

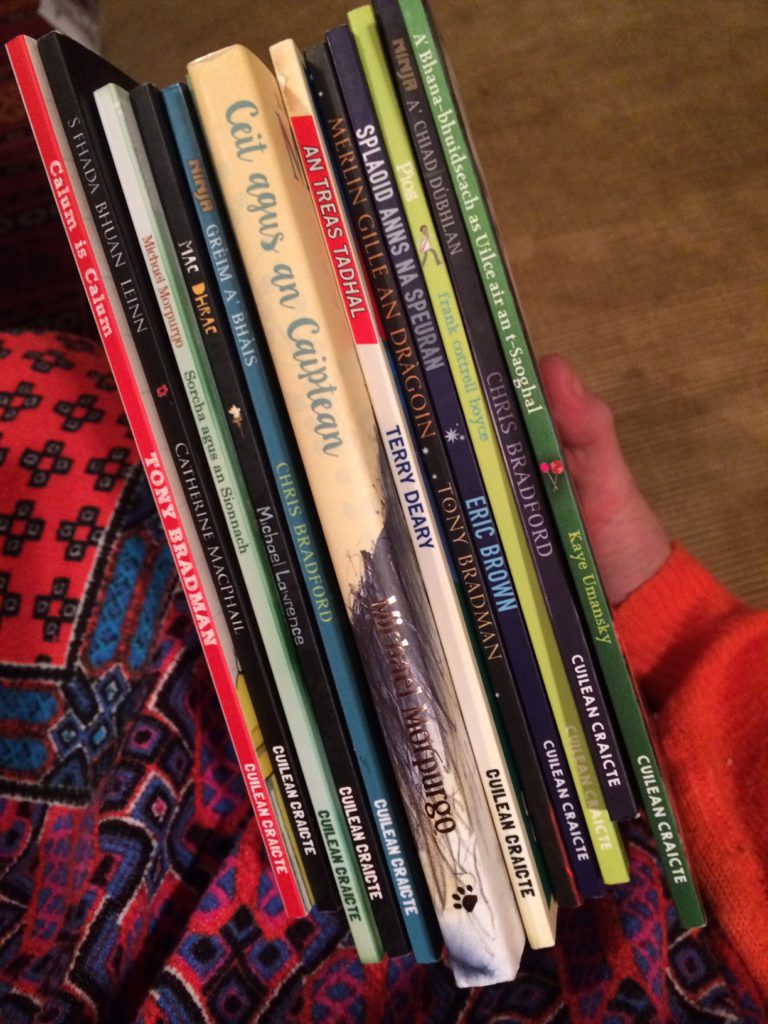

Màiri Kidd is a writer, publisher and literary developer. She was in charge of literature at Creative Scotland and among the organizations and book companies she headed are Stòrlann Nàiseanta na Gàidhlig, Seven Stories the National Center for Children’s Books and Barrington Stoke. Màiri says, however, that the best thing she’s ever done in terms of books is to put Oor Wullie (along with Donald William Stewart) in Gaelic as part of the voluntary publishing group ‘Cuilean Craicte ‘.

To mark Seachdain na Gàidhlig (World Gaelic Week) in 2022, the Futures Forum asked several Gaelic speakers to share their views of the future. The project, run with support from the Scottish Parliament’s Gaelic Officers, aimed to contribute to a vision shared at a Futures Forum event on the future of Gaelic in 2019: a Scotland where “Gaelic is visible and audible in public life, with Gaelic routinely used for non-Gaelic issues”.

Scotland’s Futures Forum exists to encourage debate on Scotland’s long-term future, and we aim to share a range of perspectives. The views expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the Futures Forum’s views.