Future Schooling, Education and Learning: The Economic Context

Scotland 2030: Goodison Group in Scotland Forum Debate

On 5 September 2017, the Goodison Group in Scotland and the Futures Forum continued their on-going investigation into education and learning in the future with a debate in the Scottish Parliament on how the economy might influence, enhance or disrupt schooling, education and learning in 2030 and beyond.

Read the Future Schooling, Education and Learning – the Economic Context: Event Report

To stimulate the debate, Professor David Bell was invited to offer his views on the relationship between economic progress and lifelong learning.

Presentation: Professor David Bell

Professor Bell opened his presentation by suggesting that, in exploring our future learning, rather than asking questions about who, where, when and how we educate our children and young people, we should take a step back and consider our ambitions for Scotland as a whole in 2030. In his view that was a fair, just, stable social and political environment, as well as a strong economy.

In order to transition to that future, Professor Bell argued that we needed to review the available evidence and then use that evidence to adapt existing policies and incentivize behaviour change.

Based on evidence from the OECD on how Scotland is performing relative to other countries in terms of science, maths and reading, he suggested that Scotland is not currently on the right trajectory to acquire the necessary skills base for the economy we want in 2030. To back up his assertion, Professor Bell referred to the work of Eric Hanushek which demonstrates the strong correlation between such metrics and economic outcomes. He also highlighted that, although the attainment gap in Scotland is narrowing, it is doing so at a slow pace.

While the evidence states that teacher quality is the single most important determinant affecting pupil attainment, Professor Bell suggested that developing the skills needed to support a strong economy should not be the sole responsibility of the education sector, but must also consider the role of the family and wider societal factors.

He went on to highlight the example of Germany, where the apprenticeship system is a ‘gigantic microeconomic management exercise’ that involves all relevant stakeholders, including local employers and multinational companies. Moreover, in Germany far fewer people enter university while vocational training plays a critical role in shaping the national economic strategy.

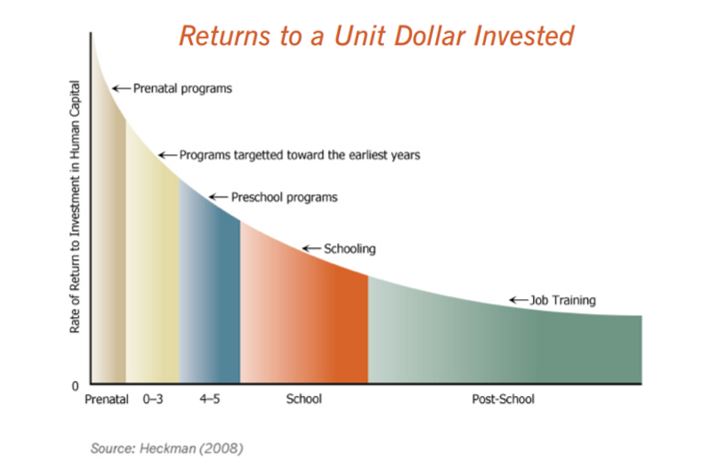

In terms of where to target our resources, Professor Bell cited evidence that highlights how pounds invested early (i.e. in the early years) give far better returns with respect to skills development, than money invested later. He also referred to the field of epigenetics where the research suggests that adverse conditions in early life can severely impact on the developing brain. However, he warned that early years interventions should be designed after careful evaluation of the evidence to ensure they yield effective and additional benefits. Professor Bell concluded by stating that, although thinking about 2030 now is a welcome development, he believed Scotland had yet to get on the right trajectory to ensure we have the right skills base for the 2030 economy.

Discussion

The discussion began with a comment that, in order for Scotland to develop the right skills base, communication had to be improved with the relevant key stakeholders, particularly employers who currently appeared to have no effective voice in discussions and skills. This was a significant loss. In contrast, it was suggested that universities had become better at being accountable for the employability of their graduates, although issues remain around the quality of jobs that some graduates enter.

The example of Germany was highlighted again as a country where employers pay towards three-year apprenticeships and therefore have a voice at the table. However, it was suggested that both SQA and the colleges in Scotland have had good relationships with employers, and that colleges in particular would be well placed to take forward the skills agenda if they received better support from the Scottish Government and other statutory agencies.

While it is a tough ask to predict a country’s future skills base and economy, it was noted that the Scottish economy had been in a state of flux for some time, making economic forecasts particularly difficult, and that Brexit has brought a distinct challenge to predicting future demographics and migration patterns. Where there are data to help with such projections, it was suggested that they largely focus on the health and education sectors, although others countered that the Scottish public sector has good datasets but that they are not used effectively to inform policy.

It was suggested that Scotland needs to be able to offer a strong skills base if it is to attract inward investment, particularly given the decline of the oil and financial services sectors, both of which were big graduate employers. There was a suggestion that we also need to think beyond Scotland to the contribution that graduates can make to the global economy, and that equipping young people with the right cognitive and non-cognitive skills was the only way to address the intergenerational income gap.

Background information on the GGiS project is available on the Future Schooling, Learning and Education Approaches homepage.