Scotland 2030: Leadership in Education

On Tuesday 12 March 2019, the Futures Forum and the Goodison Group in Scotland continued their exploration of schooling and learning in the future.

Bringing together representatives from business, government and education, this event focused on leadership in education and featured a contribution from Professor Graham Donaldson.

The seminar built on previous events from which scenarios of education in 2030 have been developed.

The scenarios and more information about the project are available on the Futures Forum website.

The seminar was chaired by Sir Andrew Cubie, Scotland’s Futures Forum director.

Presentation

Professor Graham Donaldson, First Minister of Scotland’s International Council of Education Advisers

Professor Donaldson opened by stating that history will judge us on the decisions we make during these turbulent times, especially those made in relation to teaching and learning. A key challenge we face is responding to immediate issues while seeking to prepare young people for a future that will extend through this century and into the next. He suggested that, ironically, we need to question what worked in the past if we are to plan for a better future.

Using quotes from a range of global politicians and educators, he illustrated that Scotland is not alone in grappling with defining what schools are for, while recognising that to do nothing is not a credible option.

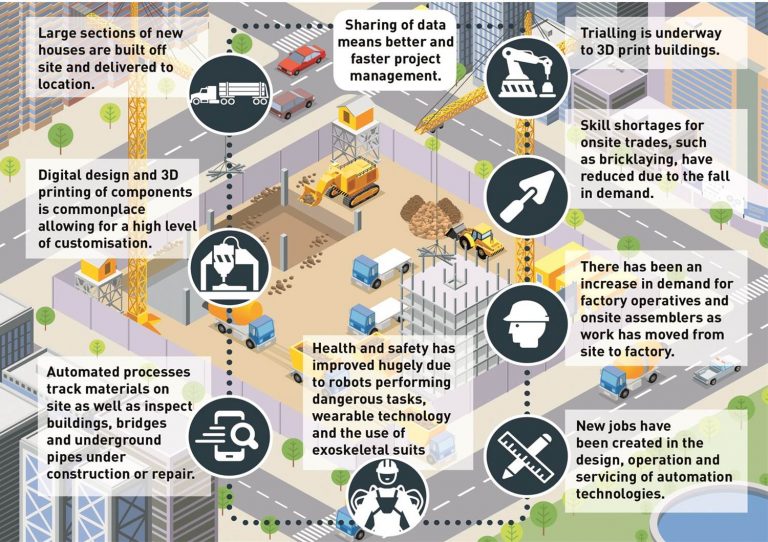

The context within which these debates are happening is characterised by uncertainty, ambiguity, inequality, and complexity. For example, we have: the need to harness technology to serve rather than drive; the new skills and dispositions required for very different economies and workplaces; the likelihood of more direct forms of democracy which will ask citizens to engage with highly complex issues; and the opportunity for more collaborative learning through greater connectivity.

Given that we are less certain about the world that our young people will be moving into, Professor Donaldson suggested that schools will need to prioritise deeper conceptual learning and skills, associated with application and creativity, over the acquisition of increasing amounts of detailed knowledge; together with the challenge of teaching pupils how to learn more collaboratively. In addition, he argued that it will be particularly important for pupils to learn how to develop their own values and ethical positions if they are to engage fully with complex issues. Young people will also need the personal and social attributes for their own wellbeing and for the development of positive relationships.

Professor Donaldson noted that Scotland was one of the first countries to generate a national debate that encouraged different thinking about the role of schools, which ultimately led to Curriculum for Excellence in 2004. With its emphasis on building the capacities of young people, rather than the acquisition of academic learning alone, the curriculum was seen as very imaginative in its time.

While reviews of Curriculum for Excellence by organisations like the OECD and Scotland’s International Council of Education Advisers (ICEA) have been largely positive, they have also suggested that some of its original policy aspirations have been frustrated for want of an explicit theory of change and by metrics that focus on a narrow subset of goals rather than the full development of the curriculum’s four capacities. Given that the lifecycle of a curriculum is often less than 15 years, Professor Donaldson asked whether it was now time for Scotland to revisit its curriculum assumptions in the context of the complex forces that are likely to characterise third decade of the century and beyond.

In moving on to talk about theories of change, he argued that if ownership of change is not secured at the point at which it is going to be delivered, we are likely to fall short of embedding its fundamental aspirations. The question is how to engage leaders and teachers in shaping change while ensuring such changes don’t lead to an incoherent and atomised education system.

Drawing on work by Johnston, Coughlin and Berger (2014 ‘Leading in Complexity’), Professor Donaldson suggested that to answer that question, we need to determine the nature of the change we want to see:

- simple change, linear cause and effect which is easy to implement by adopting best practice;

- complicated change which is more difficult to realise because the cause and effect is harder to identify but can be addressed with systematic and evidence based approaches ; or

- complex change, where the complexity of the context makes adopting best practice ineffective.

He suggested that policymakers tend to focus on simple and complicated change, despite complex change being more reflective of the world in which we live. As such, in order to lead change there needs to be a shift from a ‘mind the gap’ approach to one that encourages ownership and recognises that there is not one preconceived right answer.

Professor Donaldson used a metaphor to further illustrate this point, by stating that we needed to move from thinking of schools as ‘franchises,’ where quality is defined as faithful reproduction of a single view, to a process where we learn through strategic exploration of agreed goals.

Such an approach needs to: clearly set out the values and nature of the change we want to see; recognise the complexity and unpredictability of the world we live in; involve a better understanding of the international, national and local context; and recognise that the ecosystem of education sits within a broader set of interconnected ecosystems. We also have to have the humility to recognise that as no one source has the right answer, we need to engage all the stakeholders to ensure change is a collaborative process.

Professor Donaldson saw important aspects of Scotland’s developing approach to education as providing a good basis for the kind of imaginative and meaningful change he was describing. He summed up by restating that context matters, that all types of change need to be addressed and that policymakers need to develop a common vision that can be shaped by teachers and schools. He went on to conclude that if we pursue collaborative learning, rather than high-stakes accountability or a competitive market, to bring about the change required, we have the prospect of creating a rich and challenging environment for our young people.

Discussion

Review of national curriculum

The discussion opened with a question around what Curriculum for Excellence might look like if it were to be designed today. It was suggested that Scotland could learn from Wales, where over 140 ‘pioneer schools’ have had direct input into the recent review of their curriculum. This has given the profession greater ownership of its development, which should in turn give it greater credibility and lead to more engaged practitioners when it is rolled out nationally.

If Scotland were to look again its national curriculum, it would also need to review the teaching of literacy, particularly how we teach writing in a world of voice-animated software and spell-checkers. Likewise, the nature of reading is changing with a greater volume of illustrated, condensed texts, where hyperlinks and animation are common for onscreen texts. The challenge will be in recognising these changes while maintaining a means of developing a child’s capacity for sequential linear thought.

It was also noted that there is also an urgent need to revisit how children with additional support needs are supported within the classroom.

Measuring success

In a discussion on measuring success, questions were asked around how we can measure whether we are going in the right direction, and if we are to have metrics, who should devise them. It was agreed that while any metrics should be seen as appropriate by all those who have a stake in the system, it was important to establish a range of measures to reflect the full scope of our ambitions. Moreover it was agreed that any ambition for our schools must not be constrained by concerns around how we measure success or by the use of inappropriate metrics. In addition, it was highlighted that evidence suggests that formal testing at a young age to measure ‘success’ can constrain learning for young children.

There was agreement that we need to move from a system that measures success for accountability purposes, to one that tolerates risk and engenders trust. In this context we need to think about how we use the Inspectorate to engender a genuine learning culture within schools that supports teachers to learn from their mistakes.

Incentivising teachers

It was noted that a culture that only rewards external perceptions of success also affects teachers’ morale. While the system needs to acknowledge and reward teachers who go the extra mile, this could be realised through greater professional autonomy and peer support mechanisms and through more imaginative thinking around what schools are for.

Given the importance of good teachers, it was suggested that leaders need to prioritise teacher quality over other conditions, such as class size. It was also suggested that there should be more space for continuous professional development (CPD) within the working week, particularly as teachers may well have to reinvent themselves two or three times over a 40 plus-year career.

A question was asked about how teachers could be encouraged to see themselves as agents of change. One suggestion was for teachers to engage in the ‘middle space’ between national government and schools that has started to open up as a result of reduced central capacity in local authorities, and/or through engaging with the Regional Collaboratives. It was noted that we also need to look at public governance and recognise that established hierarchies are not going to serve us well in an increasingly complex context.

It was suggested that we should also be seeking to create the conditions for children to see themselves as agents of change so they feel some element of control within an increasingly unpredictable world.

Managing change

The theme of decision making in a complex world was revisited with a question around the challenge that many school leaders face in responding to change, given its increasingly fast-paced nature.

One response is to simply agree objectives and allow the system to find different ways to meet those objectives. With such an approach, ownership of the change needs to be closer to those who are delivering it and delivered in a culture of collective learning. However, it was noted that a balance had to be struck between autonomy and strategic consistency to avoid the emergence of an atomised system with all the negative consequences that would entail.

Early years

The discussion finished with a point about school leaders recognising the importance of play-based learning, particularly but not exclusively within the early years curriculum. Some evolutionary biologists believe the need for a child to play is part of their biology and brain. On this theme, one contributor highlighted there was a need to ensure we create environments that allow play to help children in early childhood realise their ‘biologically primary knowledge’ (Geary 2008, The Origin of the Mind), which includes language skills. It was also argued that play-based pedagogy was seen as particularly important given the children’s increasingly sedentary lifestyles and the amount of time they spend on screens.

Following the discussion on the need to review how we teach literacy, it was suggested that it will be increasingly important to focus in the early years on speaking and listening to support young children with the conscious processing of information.

Next Steps

There will be two further debates this year exploring the theme of leadership in education.

The discussions from these debates will feed into a scenario or range of scenarios with a set of provocations or questions which will be shared with policymakers.

Graham Donaldson

A former teacher, Graham Donaldson headed Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education (HMIE) from 2002 to 2010. He radically reformed the approach to inspection, combining external accountability with self-evaluation and capacity building. As chief professional adviser to Ministers on education, he has taken a leading role in a number of major reform programmes.

Following retirement from HMIE, his report ‘Teaching Scotland’s Future’ (2011), made 50 recommendations about teacher education in Scotland which have all been accepted by the Government and are the subject of an ongoing reform programme. He has also undertaken a review of the national curriculum in Wales and the 68 recommendations in his radical report, ‘Successful Futures’ (2015), have also been accepted in full and embodied in a major, long-term reform programme.

Graham has worked as an international expert for OECD, participating in reviews of education in Australia, Portugal and Sweden. He was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath by the Queen in 2009 and given the Robert Owen Award as an Inspirational Educator by the Scottish Government in September 2015.

In addition to various forms of consultancy and continuing to act periodically as an international expert to OECD projects, he was appointed as an Honorary Professor in Glasgow University in 2011 and an adviser to the Minister for Education and Skills in Wales in 2015. Graham is also a member of the First Minister of Scotland’s International Council of Education Advisers (2016).

?Hearing from Sir Andrew Cubie ahead of Graham Donaldson’s presentation @ScotParl on the future of Scottish Education. pic.twitter.com/UQ8aennQHw

— Jenny Gilruth (@JennyGilruth) March 12, 2019