Scotland 2030: Carbon Positive Jobs

Wednesday 5 February 2020, at the Scottish Parliament

What jobs will there be in a net zero Scotland?

With a climate emergency to respond to while new technology pushes at boundaries and disrupts our lives, many jobs in Scotland will change or disappear completely. New jobs will also emerge.

How can we ensure these jobs support the future of our planet?

Introduction

This debate on carbon positive jobs, held in partnership with the Edinburgh Hub of the Global Shapers Community and chaired by Maurice Golden MSP, explored how innovation and sustainability will shape how we work in the future.

Participants heard from Teresa Bray, Chief Executive of Changeworks, Georgia Stewart, chief executive of ethical finance company Tumelo, and Dr Simon Shackley, lecturer in climate policy, University of Edinburgh.

Highlights Video

Event Report

Panel

An accountant by trade, Teresa Bray is Chief Executive of Changeworks, an environmental charity and social enterprise that delivers on of Scotland’s most successful recycling services Additionally, it advises individuals and organisations on how to reduce their impact on the environment.

Georgia Stewart is chief executive officer and co-founder of Tumelo, which works to deliver an investment system that serves both people and planet. It gives shareholders a voice by showing them exactly which companies they own so they can try to bring about change.

Dr Simon Shackley lectures on climate policy at the University of Edinburgh’s School of GeoSciences, where he runs the MSc programme in Carbon Management. His main research focus is decarbonisation of the energy system, including innovation, policy, institutional change, dialogue and values.

Chair

Maurice Golden MSP has been a Scottish Conservative and Unionist MSP since 2016 and currently serves as Shadow Cabinet Secretary for Environment, Climate Change and Land Reform. He has experience in the waste and energy sectors and is a passionate advocate for the circular economy.

Presentations

Teresa Bray, Changeworks

Teresa began by stressing that not all jobs will be carbon positive by 2030—indeed, it is not until 2045 that Scotland is aiming to reach net zero emissions, although we should see a 75% reduction by 2030. She highlighted a concern: we need to think about the type of jobs that involve looking after people, which are not going to disappear any time soon.

She said that, while there will be a role for automation, people will always need interactions with people.

Teresa went on to consider the areas in which new jobs and ways of working might be needed on Scotland’s journey to becoming net carbon positive.

- Homes will require a huge amount of work to make them energy efficient. Many plasterers and joiners currently come from within the European Union, and Teresa questioned how such jobs will be filled in future. In addition, the building trade will need more entrepreneurs to meet demand and develop different ways of working in people’s homes.

- The energy network will be very different. We are already moving away from large-scale generation assets such as big power stations towards much more dispersed methods of energy generation and storage. Innovation and new approaches will be required as we move our grid to the new structures and work out how we monetarise the benefits of energy storage.

- Land use will be different. We will continue to grow food on our land, yet we will need to use peatlands and forests as a means of carbon storage. We will need people to operate smart machines to plant millions of trees.

- Transport will see huge changes. People in cities are already deciding that there is no need to own a car. How can we make transport choices such as car clubs work smartly for people, and move away from fixed bus routes to ensure that people can get around more efficiently?

- The way we live will need to change. For example, people are already looking at their diets and reducing the number of days on which they eat meat. We will need more behaviour change specialists and influencers to change demand and persuade supermarkets to fit in with new requirements. In addition, technology has to keep pace with the need to reduce emissions and with new ways of doing things.

Teresa emphasised that, alongside specific roles in those areas, we will need policymakers, planners, project managers, marketers, data specialists and software developers. She argued that, above all, people who can engage with people will play a really important part in our future.

Using your voice as an employee

Teresa emphasised that people can use their skills to apply their own values to their work. As employees, they can decide to seek to have an impact on their employers. We have to think about how we use our voice, and people will need to be prepared to change jobs.

Using your voice as a consumer

Teresa pointed out that a lot of jobs are driven by consumer demand. We should ask ourselves whether our consumption is encouraging the creation of unsatisfactory or unrewarding jobs, and decide what sort of jobs we, as consumers, are prepared to support.

A just transition

Teresa acknowledged that it is not always possible for people to choose their jobs if they have limited skills or cannot move to other places. We need to think about how society can provide worthwhile livelihoods for those people by upskilling them or enabling them to retrain.

There will be big changes in some sectors, such as the oil and gas industry, and while there will be new jobs in carbon capture and storage, they may not be at the same level. She highlighted a key question: how can we provide a just transition for people whose jobs disappear? Jobs are an important part of people’s lives, and we need to ensure that people can contribute to wider society.

Georgia Stewart, Tumelo

In her presentation, Georgia discussed how influence and communication can shape the labour market of the future.

She described her company’s innovative work as an impact-focused financial technology start-up that aims to help retail investors and ordinary people to engage with their investments. Given that the pensions industry in the UK is worth £2.4 trillion, she argued that there is massive potential for ordinary people to make an impact in that space.

Looking specifically at future jobs, she agreed that artificial intelligence will be influential, and that automation could replace existing narrow process-driven jobs. She emphasised that, while we are aiming to achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, we will still be dealing with problems such as climate change, poverty and gender equality. How can we think more broadly about tackling those problems more efficiently?

Interconnected problems require collaborative working

Georgia’s key message was that, in order to tackle big problems such as climate change and gender inequality, we need specialists working in cross-functional collaborative teams. Given that the problems we face are complex and bigger than individual sectors or industries, collaboration is very much required.

As an example, she highlighted the situation in India in which farmers’ use of a particular medication in cows, with vultures feeding on cow carcasses, is causing various conservation, economic, healthcare, social and religious issues.

Collaborative working requires communication

Georgia pointed out that, while there will be a demand for specialists to work in specific areas, we will also need generalists with broader transferable skills—for example, people who are good at communicating. She criticised the false dichotomy that has arisen between people skills and the type of skills that are needed by software engineers, for example, and declared that the best software engineers are ‘people’ people.

Communication requires facilitation

Georgia went on to stress that, in addition to good communicators, we need facilitators who are skilled at helping people to work together. She highlighted this as a useful skill for the leaders of the businesses that will emerge in the future. A leader who is driven by purpose can build a purposeful start-up that becomes a purposeful business, but they also have to consider what drives the people who work for them and the jobs that they create, because it is essential to remember that not everyone is driven by purpose.

How do we bridge the gaps?

Georgia argued that we need to think holistically about what we want to achieve. This might involve taking the good elements in what the private sector is doing and applying them to purposeful organisations. Organisations in the City are run efficiently and productively, and there is a lot to learn from them.

She noted that, while collaboration can be interesting, it is often difficult, and being a good collaborator is a powerful skill for the future. She stressed that, as a small organisation, Tumelo is agile and can move quickly, and collaborating with NGOs that operate differently can be difficult.

The more we can bring different types of organisations closer together and bridge the gaps, the more we can start to collaborate on the big interconnected issues.

Dr Simon Shackley, University of Edinburgh

Having run the University of Edinburgh’s MSc in Carbon Management for 11 years, Simon began by describing some encouraging developments in three areas relating to his work.

New entrants

While in the past the MSc course has tended to attract those from an environmental science background with a long-term interest in sustainability, he is now seeing new entrants who have worked in other sectors and want to use the course as a stepping stone to a new career in carbon management. They see climate change as the big problem that needs to be addressed, and Simon pointed out that they bring valuable expertise in finance and skills and ask difficult but useful questions about how things are costed.

Different destinations

The MSc course has produced around 400 graduates over the past 10 years. Around half of them tend to go into carbon consultancy, advising large companies on technical areas such as life-cycle assessment, carbon footprint and carbon accounting. However, Simon identified that a growing number of graduates are going into finance and investment, where there is an increasing demand for such capability.

Global links

Simon highlighted a trend of increasing internationalisation, with many new students coming from China, among other countries. He argued that that is helpful, given that China will be responsible for a very large percentage of the world’s emissions. Students will understand and think about all these issues, and take their learning back home. However, he noted that we are currently not so good at maintaining links with China to make sure that that learning is being used to its full potential.

Simon concluded by focusing on two areas for action:

1. Improve institutional capabilities.

The raft of energy efficiency programmes over the past 40 years has been somewhat successful, but we need to step up our game massively to get to net zero. We need to improve our institutional capabilities: our ability to work out the design of programmes, measures and policies, how to implement them and how to evaluate, monitor and learn from the experience. There will be fantastic career options opening up in that area, as there will be massive demand.

2. Expand engagement.

Tackling major issues requires skills not only in designing effective programmes, but in engagement. How do we get car users to start using their cars less? How do we get people to stop taking so many international flights? We are lacking the capability to engage with people beyond the usual suspects, and we need to reach communities for whom engagement may be an alien concept. It can be done—there are examples in other areas—but it requires a whole new skill set and a raft of people with the capability to understand how to communicate with various constituencies, including the affluent, that have not always been engaged.

Discussion

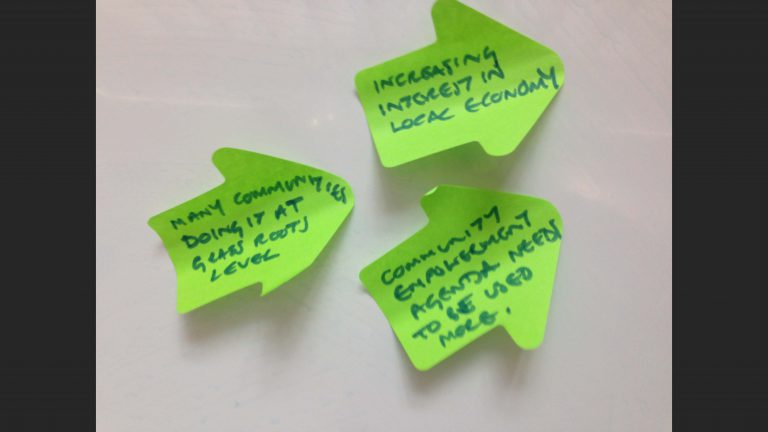

In a wide-ranging discussion, participants explored a number of key themes as building blocks for a strategy around carbon positive jobs. Interlinking aspects such as engagement, education and training, influence, risk-taking, flexibility and collaboration were discussed in term of their relevance for individuals and at an organisational level.

At the heart of the discussion was an acknowledgement of the power of individuals as consumers and citizens to effect change, and the need for engagement and inclusion to bring everyone on board in order to move forward.

Making an impact

There was general agreement that people have agency: they can decide what they do and how they contribute to shaping the future labour market. The discussion focused on the importance of ensuring that people understand the potential impact they can have on society as a consumer, shareholder or employee, or in running their own business.

The question of how influence relates to behaviour change, and how that is bound up with the development of carbon positive jobs, was explored. Participants discussed the idea of using social pressure as a way to shape the job market and encourage sustainable investment. How do we turn people’s natural desire for social kudos and reputational gain to the benefit of society and sustainability goals?

It was argued that individuals can create change in large companies, not only as employees but as discerning job-seekers, as employers will be forced to be more purposeful in order to acquire talent.

It was pointed out that employees in all areas of a company, not just those in sustainability-related jobs, can play a pivotal role. Participants also discussed how we can get those at the top to change their approach. It was posited that senior executives are often influenced by their own children, as well as by wider movements such as the climate school strikes.

Individuals can also have an influence as shareholders in making decisions about which direction a business goes in; companies such as Tumelo provide greater transparency to enable shareholders to exercise influence in that way.

Do people have more avenues for expression as consumers than as citizens? It was noted that consumers have the power to demand more information on the carbon impact of what is consumed.

The importance of holding people to account was emphasised, and it was highlighted that responsibility for doing so does not belong to any one group—it is something that we all need to do in different ways. We can no longer rely on traditional forms of accountability; the process requires more diverse routes, and we need to get more people involved in bringing influence to bear.

Bringing people on board

Building carbon positive jobs for the future will involve big changes, and just transition requires engagement to get everyone involved. Concerns were raised about how the participative element feeds into the system, but on a positive note it was highlighted that there would be specific job opportunities involving communication and facilitation.

The point was made that engagement will be crucial in the adaptations that will be needed as we move towards 2030. It was suggested that infrastructural change needs to be done in a more consultative way, and citizens’ assemblies were mentioned as an option.

Participants discussed how to enable people to see that it is important to provide pressure. It was claimed that the importance of user experience design has been underemphasised.

In some areas, a place-based approach has been adopted, given that people are influenced to a great extent by neighbours and friends. Participants discussed the need for a sophisticated approach, not just a hair-shirt approach, for which different skills will be required.

Skills for the future

Given our ambitions for innovation and carbon positive jobs, participants discussed whether enough training opportunities are being created in different sectors, and what skills should be built into the curriculum to develop a pipeline of future leaders.

There was some optimism about how far schools and universities have come in that regard, but it was emphasised that we need to keep young people engaged. It was asserted that there is definitely a need for more training in specific skills, especially given the shortage of people to fill technology jobs nationwide.

There was a recognition that, for small businesses, investment in training is a big risk to take, and more support is required. It was suggested that universities need to work with industry to find the best ways to educate and train people in skills for the future.

However, concerns were raised around inclusivity and access, especially given the cost of higher education. It was argued that exclusion from education can lead to people not taking up opportunities presented by new carbon positive jobs. Changing careers can be challenging and costly: how do we make opportunities accessible to more people?

It was argued that we need not only to train people for specific jobs, but to educate people more widely about the coming changes and what needs to be done to tackle climate change. What new skills do people need to build a career in what is a rapidly changing field?

In a sense we do not yet know, given that technologies and solutions to big issues are still emerging. Nonetheless, participants agreed that there needs to be a willingness to do things differently, so we need to educate people to be more flexible in their approach to the world of work in order that they can take advantage of new jobs and opportunities as they arise.

A dynamic approach

Flexibility and adaptability was also considered to be important at an organisational and sectoral level, and the concept of ‘nimbleness’ was highlighted. It was argued that while the private sector’s nimble approach has an important part to play, that does not mean that NGOs cannot be nimble.

It was suggested that such an approach can be difficult in the public sector, given the sheer size of organisations and the chain of accountability. Participants suggested there is a risk-averse culture in Scotland, and a safety-first approach makes it difficult for us to address big issues.

Attention was drawn once again to possibilities for new jobs relating to influence and changing approaches, where there will be fantastic opportunities in the future. Overall, it was asserted that, as a country and a culture, we have to be prepared to take risks—if you are never allowed to fail, you are never allowed to learn.

Working together

Collaboration is important, given the interconnected nature of the big issues highlighted in the presentations. Participants observed that collaboration can be difficult when organisations and sectors have differing attitudes to risk. How can we can make collaboration between the private sector and NGOs easier?

There are sometimes issues in relation to how NGOs are funded, but it was emphasised that communication and agile working skills above all are crucial in enabling people to work together across sectors.

Participants described both positive and negative experiences of cross-sector working, and agreed that it is necessary to think about how we cross those boundaries. How do we merge areas which currently feel very separate? We need to take a holistic approach to our business and our economy, or we will not stretch and move forward.

There was some discussion of how we can bring the private sector, the public sector and the third sector closer together. It was even suggested that, in future, that separation may not exist at all. It was argued that encouraging the public and private sector to work on projects in combination could be an interesting new route to follow.

Concluding thoughts

There was general agreement that, when it comes to our zero-carbon ambitions, the future is in the hands of us all.

We can all make a difference through the choices that we make in how we work, consume and live our lives.

There is a responsibility on us all to change the way that we do things, and greater collaboration and a risk-taking mindset must be at the forefront of our vision for carbon positive jobs in 2030.

Partners

The event is held in conjunction with the Edinburgh Hub of the Global Shapers Community, which is an initiative of the World Economic Forum.