Scotland 2030: A Wellbeing Economy?

Tuesday 5 February 2019, at the Scottish Parliament

In conjunction with the Scottish Parliament’s Economy, Energy and Fair Work Committee, the Futures Forum held a seminar on the idea of Scotland as a wellbeing economy.

The seminar was chaired by Gordon Lindhurst MSP, convener of the Committee, and featured a presentation from Dr Katherine Trebeck, Policy and Knowledge Lead for the Wellbeing Economy Alliance Scotland, on the concept of and reasons for a wellbeing economy, and the work of WEAll Scotland.

Other members of the Wellbeing Economy Alliance Scotland also participated, with Peter Kelly from the Poverty Alliance and Andrew Cave from Baillie Gifford providing perspectives on why their organisations are involved.

Podcast

Presentation Transcript

I’ve been told to talk to you about the progress of our new organisation: the Wellbeing Economy Alliance, which rather nicely abbreviates to WEAll. First, I want to ask a brief question: why focus on the economy, and why think about redesigning the economy so that it can become purposed to deliver human and ecological wellbeing? I can go into that in a lot more detail in questions or conversation, on Twitter or by email—just let me know. I will offer a couple of brief bullet points to introduce the idea of why WEAll, and our growing membership, is saying that we need to change the way that the economy operates.

The first slide is one that I constantly come back to. It was produced by colleagues of ours—people like Ida Kubiszewski and Bob Costanza—who are members of the WEAll global community. They have come up with the idea of the genuine progress indicator, which—in a nutshell—takes gross domestic product and corrects it. It extracts some negative things that might undermine genuine progress, such as inequality, pollution or commuting, and adds in things that would contribute positively to genuine progress, such as access to green space or volunteering. They calculate that for loads of countries and track it back over decades, and compare it to gross domestic product.

As the graph shows, the two—GDP and GPI—worked fairly closely together for a while. After 1978, however, genuine progress started to flatline, whereas GDP per capita, which we use as a proxy for how a country is doing, merrily continued tracking upwards. The gap has widened, and there is a growing divergence between what mainstream measures tell us about how the economy is performing and the idea of genuine progress.

Another way of looking at that involves a new entrant on the measurement scene, which is quite a flourishing terrain. It is a really exciting development involving a group called the Social Progress Imperative, who are partners and members of the Wellbeing Economy Alliance. They take around 53 different measures of social progress, such as human rights, access to education and a free press, and tally them up on the Y axis. Along the X axis, they map GDP per capita, and then they plot the position of various countries across the two.

It is very clear that, at the early stages of economic development, more GDP per capita really matters, as you get very quick returns in terms of social progress. However, you very quickly start to get diminishing marginal returns—I learned about the concept of diminishing marginal returns in Economics 101. You can see it clearly on the slide. The more GDP per capita, the less bang for your buck you get in terms of social progress. You could easily replace the X axis on the graph with different measures for environmental impact, which starts to tail off in terms of the benefits for communities and societies.

The next slide shows some recent work conducted by ecological economists at the University of Leeds. They have taken 150 countries around the world and asked the question: “Do any of those countries actually deliver a social foundation for their citizens, lifting everyone up above a social foundation, without putting excess pressure on the planet and breaching the idea of an environmental ceiling?” You may be familiar with Kate Raworth’s doughnut concept in relation to the environmental ceiling and the social foundation. This research maps whether any countries are getting inside that doughnut and delivering socially without ruining the planet.

You can see that plenty of countries deliver by lifting many of their citizens, in an average sense, above a certain social foundation. The bad news is that they do so while transgressing environmental boundaries. There are fairly rich countries that are doing okay in terms of social progress, but at a huge cost to the environment. The countries at the bottom of the graph are not putting much pressure on the planet, but they are failing to deliver for their citizens. In the 21st century, we need countries to be in the top left-hand corner of the graph, where economies deliver social progress without putting undue pressure on the planet. The bad news is that that area of the graph is currently an empty space. Vietnam comes closest—there is huge data on that on the project’s website. It is a brilliant piece of work.

We have a situation in which we have an economic system that is not delivering in social and environmental terms. It is failing in many respects, and we can see that people around the world have a growing sense of frustration with the economic system, whether they are turning to the pill box or the ballot box. We now “wonder what to put in its place.” John Maynard Keynes wrote those words in the 1930s, but we can have a conversation now about what we can actually put in its place and how we can design a different sort of economic system.

You don’t have to look far to get a sense of what that different economy might look like. You hear about it if you sit down and have conversations with people, wherever they are in the world, and have a deliberative discussion about what really matters to them. Whenever you sit down and have a conversation, whether it is with young girls in the slums of Delhi or people in the Amazon in Brazil or in community spaces in Govan, you start to hear very familiar stories about what really matters to people.

You also hear about it if you listen to great development scholars such as Manfred Max-Neef, Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum. A whole range of development scholars are very much pointing to a similar sort of understanding about what a different economy, and different notions of progress, might look like. Recent emerging science in areas such as neuroscience, epidemiology and psychology is telling us what we know about what makes people innately human. What lights up certain areas of the brain and makes people happy or less stressed is when they are co-operating and in nature, and when they are in good relationships.

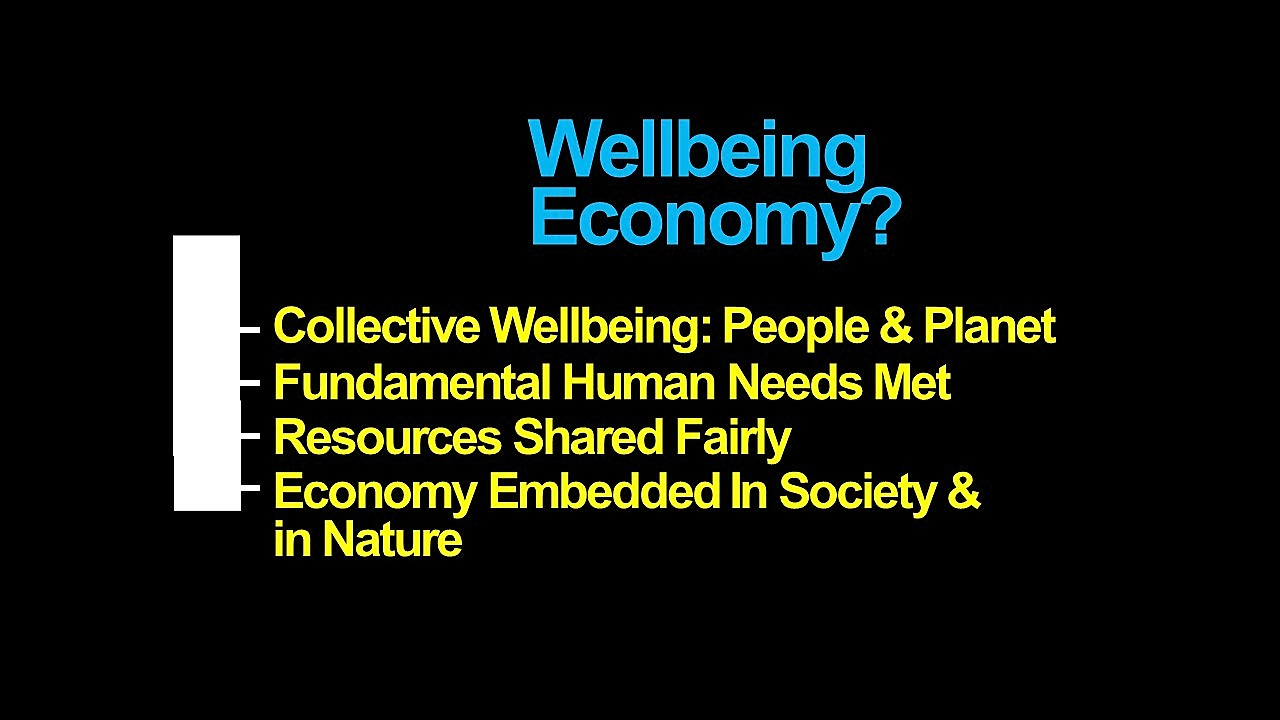

If we bring all that together, we start to get a very different picture of what the economy can be purposed for and what it can be about. For us at WEAll, and for our growing membership, it is about collective wellbeing: not just asking people how happy they are on a scale of 1 to 10, but really focusing on collective broad-based human and ecological wellbeing, ensuring that fundamental needs are met, sharing resources fairly and recognising the extent to which the economy is embedded in society and nature. That last point is brought out very powerfully in the Sustainable Development Goals.

The next slide shows what is called a wedding-cake picture, for obvious reasons. You can see how the economy is situated within society, and how both are a subset of our natural world. Too often, that is flipped on its head, and we see society and nature being put at the beck and call of the economy.

Moving to a wellbeing economy is about saying that it is not good enough just to fix, heal and redistribute at 5 o’clock in the afternoon. That is sticking plaster territory, and it is no longer fit for purpose. We are not very good at it, because we are not delivering sufficiently for people in environmental and social terms. We need to have a conversation about a very different sort of economic system that gets things right from day 1. It is about changing the way that the economy operates: who gets fair shares, and how do we create economic activity?

The next slide shows a cartoon that I’ve been using for years. It is about measuring what really matters, and focusing on growing what is important rather than on an abstract notion of growth per se.

This is a conversation that has deep roots reaching back over many decades, even prior to Robert Kennedy’s beautiful speech—we celebrated the 50th anniversary of that speech last year. A couple of years later, we had the Club of Rome talking about “The Limits to Growth”. The same year, the King of Bhutan talked about gross national happiness being more important than GDP.

I will skip ahead several decades—a lot has happened, obviously. In 2008, we had the global financial crisis, when the idea of changing the economic system was to an extent up for grabs, but the problem was that we doubled down. Conversations opened up—in the OECD, for example—around different measures of progress. In 2012, we had the UN report on a new development paradigm. In the same year, the UN unanimously passed a resolution on the development of happiness.

Just a couple of years ago, the Sustainable Development Goals were agreed. Last year, almost 240 academics wrote a public letter to the European Union to say that, instead of the growth and stability pact, we need a wellbeing and stability pact. That same year, there was an update to the Stiglitz report, in which the OECD’s group on measuring progress said that the response to the global financial crisis focused too narrowly on increasing GDP, and hence the impact in the form of acute austerity took people and the economy in the wrong direction and increased financial insecurity for citizens.

In 2018, we launched a tiny new initiative called the Wellbeing Economy Governments Group. We have also seen young people coming out of their schools to go on strike and stand up for their future. WEGo is a small initiative led by Scotland that says that we need to collaborate and work together to develop policies for human and ecological wellbeing. It was launched at the OECD wellbeing forum just last November with Joseph Stiglitz and with New Zealand and Iceland, and other countries will soon be joining.

Last year, the new organisation that I work for—the Wellbeing Economy Alliance—went live. Our theory of change is that if we work together, we can do quite extraordinary things. The slides illustrate our theory in graphic design form. We want to bring together the knowledge base around developing a different economy, and bring together narratives and different ways of talking about the economy, so that we can open up the discussion and get rid of some of the assumptions and orthodoxies that constrain us. We can then build a power base by collecting all the amazing work that is already being done to transform the economy, and we can see that flourish into economic system change.

It is about connecting, amplifying and increasing the impact of what is already happening. We are not short of ideas—it is not a step into the unknown. People are rolling up their sleeves and working every day on different agendas and different ways of understanding the economy; the problem is that those agendas are too disparate. WEAll is about connecting them and bringing them all together.

It is also about supporting the pioneers. It is about helping those folks, economies, Governments, businesses and community groups that are willing to go a little bit further and experiment to start to deliver, here and now, a different way of doing the economy. We will be supporting them and connecting them. We have their backs, and we will be using them to inspire others to replicate their work. Those pioneers demonstrate the feasibility and desirability of a different way of doing things.

The next slide is a cartoon that explains the idea of the Overton window; it was sent to me by a friend of mine in Australia who had been working on equal marriage. It shows that if we can open up the discussion, we can move people’s conversations about how the economy operates. As I said, it is also about how we talk about all this. Engaging in the conversation has to be accessible, compelling and inspiring. The conversation can’t take place only in the halls of the economic policy-wonk world that I inhabit—it has to be an accessible conversation that is open to everyday people, not just those of us who hang out in 50-page documents.

WEAll is growing. We have over 60 different members, from the small to the huge and from businesses to community groups, along with other networks. The information is all on our website if you want to dip into it and see who is joining us. We have done a lot in less than a year. We have five active clusters around research, narratives, citizens and businesses, and we have developed a guide to how citizens can make the transformation to a wellbeing economy.

We supported the launch of the Wellbeing Economy Governments project—there is a lovely documentary being made about that journey. We have started to produce a lot of knowledge products, and we have recruited 10 brilliant ambassadors. We have a lot of people rolling up their sleeves and helping on the journey. We have a growing team of research fellows and a tiny little staff team who are doing a lot of talks and appearances. Our website is growing, and we had a viral stunt in New York just last September. There are growing local hubs and local iterations of the project happening across the world.

I am most excited about the youth hubs. Young people are saying, “We want to be part of this movement—what can we do to help?” Those hubs are springing up, from the Netherlands to Uganda. The most exciting part is the Wellbeing Economy Alliance Scotland, which is a Scottish iteration of the wider global movement. Our idea is to ask not only what Scotland can do to contribute to the wider global movement, but how Scotland can benefit from being part of the growing global movement.

We are talking about the idea of “Wealth of Nations 2.0” to build the conditions for wellbeing. In Old English, the word “wealth” meant the conditions of wellbeing. What if we could reclaim the idea of wealth? What is Scotland’s real wealth? What would Scotland’s Wealth of Nations 2.0 look like in building a wellbeing economy?

We held a Wealth of Nations 2.0 event, which was quite extraordinary. We hosted it with Baillie Gifford, the Poverty Alliance and Scotland’s Futures Forum. We didn’t advertise it—we put out one email, and the event was overbooked several times over even with no advertising. There is a real appetite in Scotland for these sorts of conversations.

We were lucky to be joined by Professor Jacqueline McGlade, who is a former UN Chief Scientist. She talked to us about the relevance of the Sustainable Development Goals— she’s Scottish herself and is very excited about the idea of Scotland playing a key role in leading this conversation here and also globally. We had some great discussions about where Scotland is up to and what the bright spots are, as well as what is holding us back and what some of the limits of the conversation are. We listened intently to what the people in the room told us would be useful in moving Scotland to a wellbeing economy.

We gathered all those views together, and we have been sifting through them. We have distilled down what we want to do in taking forward our work as the Wellbeing Economy Alliance Scotland grows and builds this year. It is about creating spaces like this for discussion. That enables people—Chatham House rules or otherwise—to ask questions; to really critique the assumptions that have boxed us in around conversations about the economy thus far; and to connect with the amazing work that is already happening.

As I said, this isn’t a step into the unknown—we know what it looks like, because we see it in microcosm every day in businesses and communities and in policy-making. We want to build up and facilitate the knowledge base so that people have at their fingertips the ideas, guides, theories and practice around how to create a wellbeing economy. We want to harness the growing global movement so that Scotland can benefit from cutting-edge knowledge and ideas and be connected to the energy and all the enthusiasm that is developing around the world.

Slides

Blog

Can Scotland be a world leader in wellbeing?

Read the reflections of Jennifer Wallace, head of policy at the Carnegie UK Trust, on the seminar here:

Speaker biography

Dr Katherine Trebeck is Policy and Knowledge Lead for the Wellbeing Economy Alliance. She has over eight years’ experience in various roles with Oxfam GB – as a Senior Researcher for the Global Research Team, UK Policy Manager, and Research and Policy Advisor for Oxfam Scotland.

Katherine, with Lorenzo Fioramonti, instigated the group of Wellbeing Economy Governments; developed Oxfam’s Humankind Index; and led Oxfam’s work on a ‘human economy’.

She was Rapporteur for Club de Madrid’s Working Group on Shared Societies and Sustainability and is on the advisory board for the Centre for Understanding Sustainable Prosperity; the Living Well Within Limits project; A Good Life for All Within Planetary Boundaries; and the Economic Democracy Index project.

Katherine has Bachelor Degrees in Economics and in Politics and holds a PhD in Political Science from the Australian National University. She is Honorary Professor at the University of the West of Scotland and Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Strathclyde (based at the Fraser of Allander Institute).

Her most recent book The Economics of Arrival: Ideas for a Grown Up Economy (co-authored with Jeremy Williams) was published in January 2019.

Event participants

Participants in the seminar included MSPs, Scottish Parliament staff and members of the Wellbeing Economy Alliance Scotland as invited guests.

Background

In November, the Scottish Government launched the Wellbeing Economy Governments initiative with Iceland and New Zealand (http://wellbeingeconomygovs.org/). This network aims to facilitate the sharing of experience and expertise among officials working to embed wellbeing outcomes in economic policy. Its secretariat is run from the office of the Scottish Government’s Chief Economic Adviser.

Separately, Scotland is home to a new chapter of the global Wellbeing Economy Alliance (WE-All). WEAll exists to help bring about a transformation of the economic system, of society and of institutions so that all actors prioritise shared wellbeing on a healthy planet. In Scotland, members include global finance companies, social entrepreneurs, and campaign groups such as the Poverty Alliance.