Scotland 2030: A Citizen’s Income?

Tuesday 2 April 2019 at the Scottish Parliament

With predictions of social and economic upheaval brought about by technological and environmental changes, could a citizen’s income reduce poverty and increase people’s control over their lives? How attractive – and affordable – is it as a policy?

Using new research from Edinburgh and Heriot-Watt Universities, funded by the Scottish Universities Insight Institute, this seminar brought together perspectives from all sides of the debate to consider whether citizen’s income is a realistic solution for Scotland’s future.

Chaired by Alex Rowley MSP, Convener of the Scottish Parliament’s Cross-Party Group on Basic Income, the event opened with a presentation by Professor Mike Danson from Heriot-Watt University on the recent research project: Exploring Citizen’s Income – Research Project, before a panel discussion with Miska Simanainen from the Social Insurance Institution of Finland, Cleo Goodman from Citizen’s Basic Income Network Scotland, and Carlo Morelli, University of Dundee Business School.

Writer and performer Susie Maguire was unable to take part as planned in the session. Instead, she wrote a response – a dream – to the issue, which you can read here:

Background

The event was held in conjunction with Citizen’s Basic Income Network Scotland, which is a charity dedicated to opening up the conversation about basic income in Scotland. It supports a network of basic income advocates, providing training and supporting organisations in engaging their stakeholders on the topic.

If you’d like to learn more about basic income, you can get in touch with Citizen’s Basic Income Network Scotland by emailing team@cbin.scot or visit the website www.cbin.scot.

Highlights video

Podcast

Listen to highlights of the discussion on this Parliament podcast:

Presentations

Professor Mike Danson

Heriot-Watt University/Citizen’s Basic Income Network Scotland

At the outset of his presentation, Professor Danson noted that although the concept of a citizen’s basic income has been around for decades, it is only in the last couple of years that it has attracted significant interest.

In some countries, interest in a citizen’s income has arisen from its potential impact on labour market engagement, while in Scotland it has attracted attention as a means of tackling poverty.

In Scotland, conversations around a citizen’s income are taking place against a backdrop of low wages, low productivity, high levels of inequality, a rise in self-employment driven by the demand for more flexible labour, growing concerns about poverty, and lower spending per head of population on social security benefits than elsewhere in Northern and Western Europe.

Professor Danson highlighted that in addition to the debates that are taking place in Scotland, four local authorities (Edinburgh, Glasgow, Fife and North Ayrshire) are trialling feasibility studies which will look at the political, financial, psychological, behavioural and institutional feasibility of a basic income.

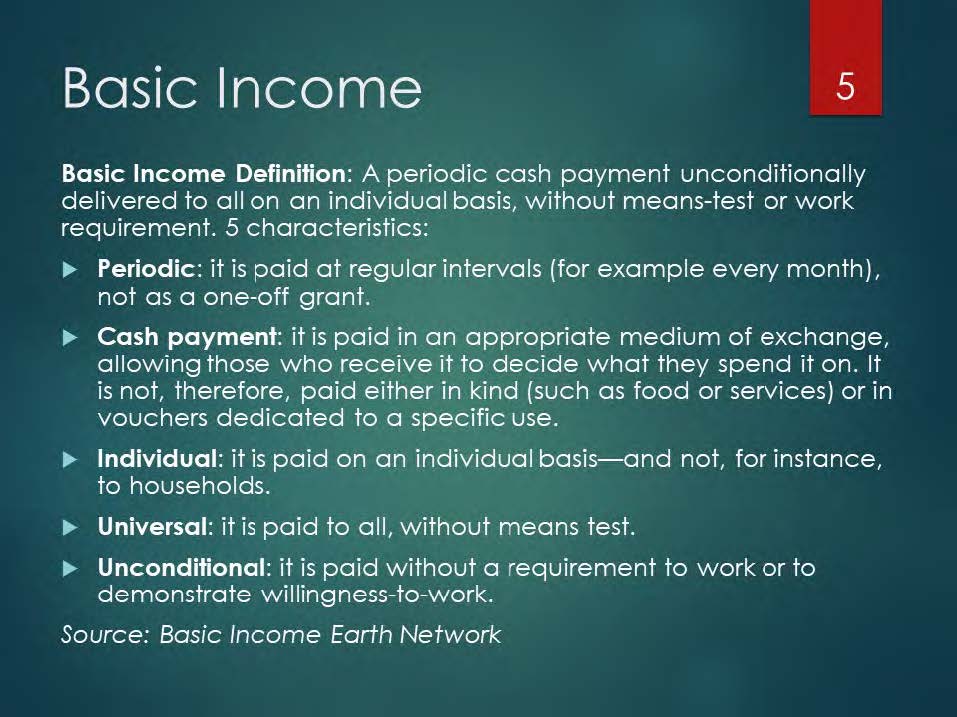

Professor Danson outlined a definition of citizen’s basic income as “a periodic cash payment unconditionally delivered to all on an individual basis without means test or work requirement”. He noted the importance of the payment being cash, rather than vouchers, not conditional on any activity, and provided to individuals rather than at a household level.

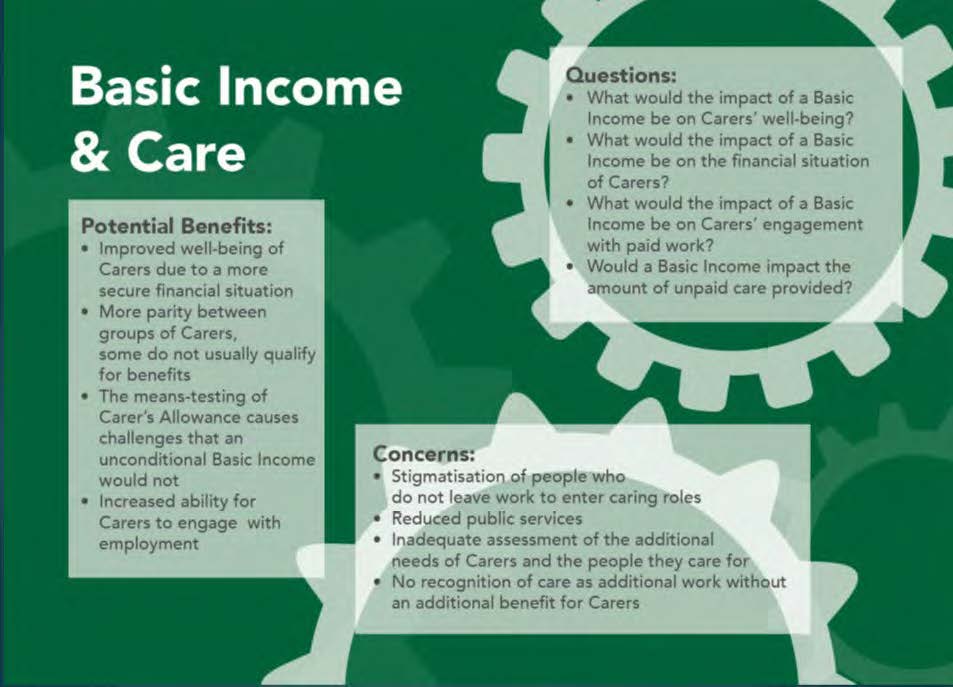

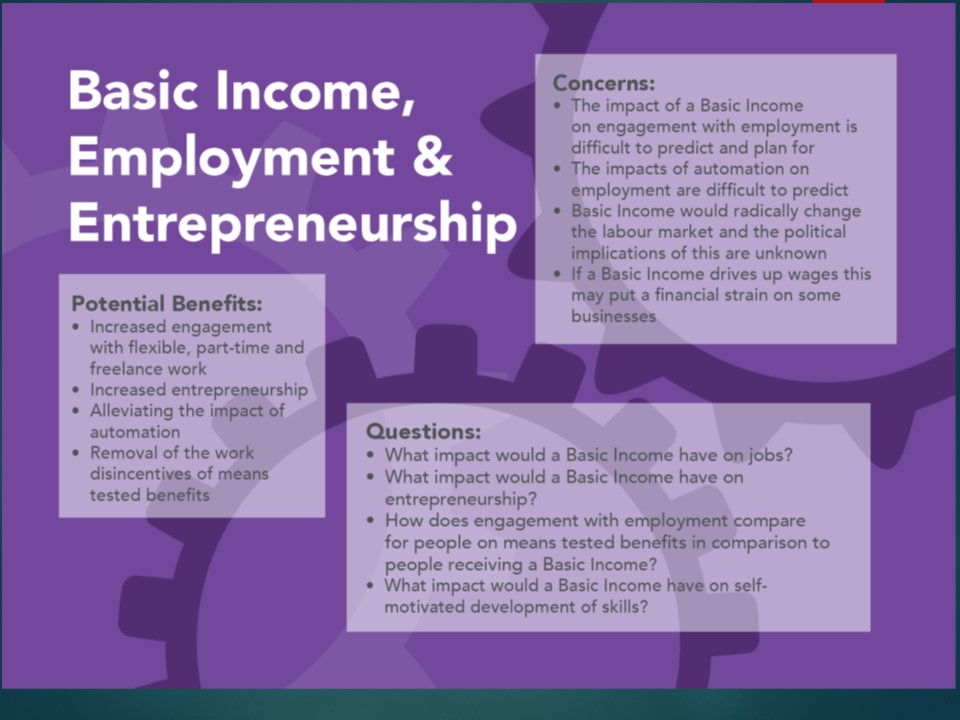

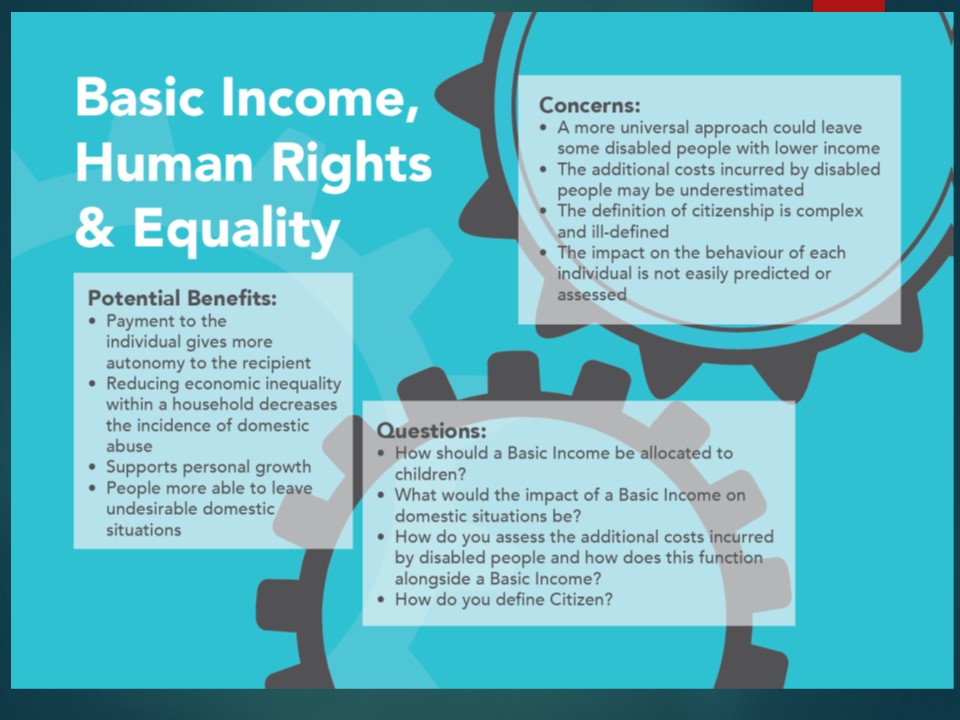

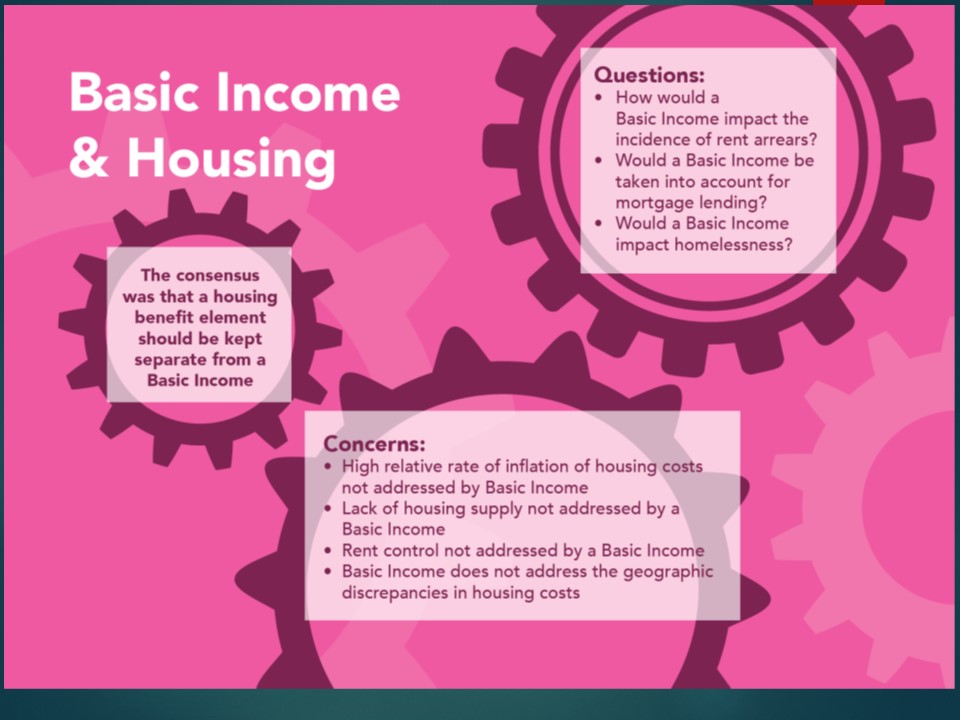

In order to explore the concept of a basic income in more depth, Citizen’s Basic Income Network Scotland ran a series of workshops in partnership with the Scottish Universities Insight Institute (SUII). These workshops considered how a citizen’s income might interact with the following policy areas: employment and entrepreneurship; housing; care; and human rights and equality.

The programme also looked at how to model, implement and evaluate any basic income model, in recognition of the significant challenges relating to what should be included in any evaluation, such as whether they should include more than impact on the labour market and individual wellbeing, as well as how such concepts should be defined.

The workshops drew in over 100 people including academics, policymakers, practitioners and members of civil society as well as people with direct experience of the issues under discussion, such as carers and those with experience of homelessness. In addition to expert speakers, each workshop deployed a sceptic to pose challenging questions, and was structured to capture the perceived benefits and concerns around the concept of a basic income as well any unanswered questions.

Professor Danson summarised some of the key findings from the workshops, which are set out in full in the report, Exploring Basic Income in Scotland.

The perceived benefits of a citizen’s income included: personal growth; reduced inequality; increased entrepreneurship and engagement with work; improved wellbeing, particularly amongst carers; and more empowered individuals, particularly more empowered women, with evidence that a citizen’s income leads to lower rates of domestic violence and higher rates of divorce.

Concerns were raised that a citizen’s income could: leave people with disabilities on a lower income; reduce public services; stigmatise people who did not give up work to become a carer; and increase wage bills and make workforce planning more difficult for small businesses.

Professor Danson noted that housing policy was a particularly complex area with a number of challenges, such as the shortage of affordable housing, which the introduction of a basic income would not resolve. This particular policy area also raised a number of challenging questions, including how a citizen’s income would interact with housing benefit.

In the other workshops, a number of broader questions were raised including the age at which individuals should be entitled to a basic income, and how ‘citizen’ might be defined. Would it include refugees and asylum seekers, and students from elsewhere?

Professor Danson concluded his presentation by stating that a citizen’s basic income offered an opportunity to establish an alternative social security system particularly in Scotland where it has garnered significant interest and support. However, he noted that, to take forward such a policy, Scotland would need to negotiate an end to means tested benefits with the UK Government and resolve a number of tax-related issues.

Discussion

A panel-led discussion followed the presentation, featuring:

- Miska Simanainen from the Social Insurance Institution of Finland

- Cleo Goodman from Citizen’s Basic Income Network Scotland

- Carlo Morelli, University of Dundee Business School

Citizen’s income as a means of addressing poverty

Although concerns around growing inequality have been a key driver behind the interest in basic income in Scotland, caution was urged about viewing it as the only means of addressing poverty or other adverse outcomes associated with the austerity agenda. It was argued that the UK’s social security system is broken and that implementing a citizen’s income will not in itself fix it.

Given the interest in the notion of a citizen’s income from neoliberals, such as the Institute of Economic Affairs, it was suggested that there was also a danger of basic income being advocated and used to subsidise rents in the private rented sector and low wages. As such, it was argued that a citizen’s income could merely facilitate a transfer of assets from the poorest to the wealthy and that we should therefore also be looking at making the tax system more progressive, including shifting more of the tax burden from labour to capital.

Labour market drivers

Basic income has a number of unlikely champions in the United States, including those who have made their money in the tech industry, such as Bill Gates. A discussion followed about whether we should be cynical of their motives or whether such people have the foresight to understand the need for alternative policy responses to the labour market changes we are likely to see as a result of automation.

Some scepticism was expressed about the extent to which we will see a significant loss of jobs through automation and therefore whether this should be the main driver for the implementation of basic income. It was argued that rather than a loss of jobs per se, what we are likely to see is a further redistribution of jobs to overseas labour markets. It was further suggested that we should be careful about how a basic income is framed to ensure it is seen as a human right rather than just a means of encouraging more participation in the labour market.

Automation was not a driver for the basic income pilot that was established in Finland; any significant changes in Finland’s labour market relate more to the younger generation who are now more likely to be working in a number of part-time jobs for different employers.

Financing a citizen’s income

A number of questions were raised around the cost of implementing a citizen’s income and how it would be funded. The Citizen’s Basic Income Network believe that a citizen’s income should meet all of an individual’s basic needs (food, clothing and shelter), but are wary of quoting a single figure as the overall cost would depend on the model adopted; CBINS is keen to keep the discussion open and for people to look at all options without focusing narrowly on cost.

However, one report was quoted as putting the cost of the policy at £61-£100 per person per week. It was further suggested that the current social security budget would need to double to implement a citizen’s income, and that without significantly increasing the current social security budget, any model adopted would simply transfer poverty from one group to another.

There was no shortage of ideas around how a citizen’s income might be funded. Suggestions included: introducing a more progressive tax system; replacing the personal tax allowance; implementing a land value tax; and combining a citizen’s income with land reform to establish a ‘Commons Good Agency’ which could redistribute the revenues from land rents. It was also suggested that there is scope to make some savings in the current system through ending the assessments which determine who qualifies for benefits.

It was noted that unconditionality, a key feature of a citizen’s income, was particularly welcomed by people with disabilities who are subjected to ongoing assessments under the current system. However, it was noted that a citizen’s income fails to recognise the simple fact that everyone in the system is not the same and, as such, would not cover the additional costs of people with disabilities or those with caring responsibilities.

Moreover, a citizen’s income does not attempt to compensate those who are excluded from the labour market (because of their disability or caring responsibility) in the way that the current system does. It was argued that if universal credit had done what it had initially promised to do (make everyone in the system better off), then we would not now be talking about basic income.

Learning lessons from pilots and feasibility studies

Finland’s pilot of a citizen’s income finished in December 2018 and is currently being evaluated. It set the individual rate at the level of its minimal benefit which made it easier to implement and to draw in more beneficiaries from outside the current system.

It has been estimated that such a scheme would be cost neutral if it were rolled out across the Finland due to the increased taxes collected from the additional earned income. However, caution was urged on generalising from the findings of this pilot to other populations and other countries.

On the back of their experience in Finland, Miska Simanainen advised that it was important to consider whether a similar result could be achieved through making small changes to the current social security system rather than attempting to bring about the dramatic changes required of a citizen’s income. In addition, he urged ensuring that whatever model is adopted has cross party support.

It was noted that while any pilots undertaken in the UK would be affected by the regulations of the Department of Work and Pensions (such as that any income earned over a certain threshold will be clawed back) the participants in the four feasibility studies being undertaken in Scotland have been reassured that they will not be any worse off.

A Scottish citizen’s income?

The participative nature of the consultation that the Citizen’s Basic Income Network Scotland undertook with SUUI has drawn praise from within Scotland and from overseas, and it offers a valuable contribution to the debate. There was general agreement that cost should not be a deterrent to exploring the potential of implementing a citizen’s income in Scotland, where in general there is a less negative attitude towards those claiming social security benefits.

In response to a question about whether Scotland could implement a citizen’s basic income without independence, it was suggested that welfare would need to be wholly devolved so that any conditionality attached to social security benefits could be revoked.

It was suggested that as a society we have become more cautious about taking forward bold policies, but that we should take inspiration from Nye Bevan who had the vision to ignore his critics and implement Beveridge’s recommendations to create the welfare state and the National Health Service.

Other Resources

- House of Lords Library (July 2021) Current Affairs Digest: Social Policy

- Nature (July 2020) Pandemic speeds largest test yet of universal basic income

- New Scientist (6 May 2020) Universal basic income seems to improve employment and well-being

Partners

The event was held in conjunction with Citizen’s Basic Income Network (CBIN) Scotland, a charity dedicated to opening up the conversation about basic income in Scotland. It supports a network of basic income advocates, providing training and supporting organisations in engaging their stakeholders on the topic. Learn more about basic income from CBIN Scotland.