Scotland 2030: Growing Older in Future Scotland

Wednesday 3 October 2018, at the Scottish Parliament

The Futures Forum continued its investigation into life in the future with a discussion on growing older in 2030 and beyond.

Chaired by Ross Greer MSP, this session focused on the role of older people in our society and the aspirations we have for our later years.

Participants heard from Professor David Bell and Dr Elaine Douglas of the University of Stirling’s HAGiS (Healthy Ageing in Scotland) study about how an older population may change Scottish society, before discussing the implications and considering a key question: what will it mean to grow older in Scotland in 2030 and beyond?

Panel members

Professor David Bell

David has been Professor of Economics at the University of Stirling since 1990. He has also held numerous other roles, including as budget adviser to the Scottish Parliament’s Finance Committee and special adviser to the House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee. He is the principal investigator for the HAGIS project.

David presented on issues relating to Scotland’s ageing society in the context of insights from HAGIS.

Dr Elaine Douglas

Elaine is a research fellow with HAGIS. With a background in public health, her main research interests include the social and economic determinants of health behaviours and understanding pathways to improve people’s lives.

Elaine presented on the HAGIS study’s methodology and data.

Robin Lloyd-Jones

Robin is a writer of both fiction and non-fiction; he has worked in education and as a creative writing tutor at the University of Glasgow. He recently published the book “Autumn Voices”, which is based on interviews with 19 Scottish writers over 70 and examines creativity in later years. His forthcoming book is “The New Frontier: Making a Difference in Later Life”.

Robert McCall

Robert is a member of the Communic18 initiative. He works as a co-design champion for the Year of Young People, which aims to celebrate Scotland’s young people through a series of activities and events. He is also the Member of the Scottish Youth Parliament for Perthshire North.

Watch the presentation:

Read the slides:

David and Elaine’s slides are available here: Healthy Ageing in Scotland – Presentation Slides.

Event report

Professor David Bell, Healthy Ageing in Scotland

To begin, David emphasised the importance of statistics and data in providing sound evidence on which to base policy for 2030. He offered some general observations about Scotland’s ageing society, stating that older people:

- Hold most of the wealth. Housing and pensions are the major form of wealth-holding in the UK, while savings constitute a much smaller proportion.

- Typically have higher incomes than the young. They have more experience and human capital, and they joined the labour market in the 1970s and 1980s when it was more buoyant in comparison with today.

- Pay more tax through income tax and VAT than those aged under 50—an important point, given that the Scottish Parliament is getting more powers in that area.

- Use more public services and interact more with the state than the young do. That includes receiving health and social care and social security benefits, most of which relate to disability and to the state pension, for which responsibility rests with the UK Government.

- Are more likely to vote. The new political schism may now be between old and young rather than left and right.

Changing demographics

Looking to the future, David highlighted projected growth trends from 2016 to 2041 across different age groups to give a flavour of how Scotland’s demography will change.

- For those aged from zero to 64, there will be no growth, even assuming that in-migration from the European Union continues.

- For those aged 65 to 70, there will be growth that tails off towards the end of the period as the baby boomer generation moves through.

- Those aged 80 and over will experience the most rapid growth. For every 100 people in this group in 2016 there will be 180 by 2041, which equates to an 80% increase.

David went on to look at how the state spends money on people over their lifetimes and how they pay taxes. At the start of life, the state does not spend much on people. Education causes a blip when they are young, before they enter the labour market and begin to pay tax. At age 60, a number of factors kick in. Those include spending on health, long-term care—mostly among older old people—and welfare, mainly in the form of the state pension.

Breaking the social contract?

As David pointed out, the key element is the social contract: older people use a variety of public services, but they contribute to those services while they are of working age. The changing situation presents difficulties in that respect, which raises issues around intergenerational fairness. David argued that, if we want to maintain the current structure, there must be a contract between the generations that involves reciprocity in paying into the system.

In previous years, the social contract was cemented by the fact that each generation earned more than their predecessors. David highlighted five groups:

- Greatest generation

- Silent generation

- Baby boomers

- Generation X

- Millennials

Each of the first three generations earned more than the last. However, from Generation X onwards, the trend began to change, and millennials are on course to earn slightly less than Generation X. That raises an issue that Scottish society has not confronted for a long time: the possibility that children may earn less than their parents during their lifetime.

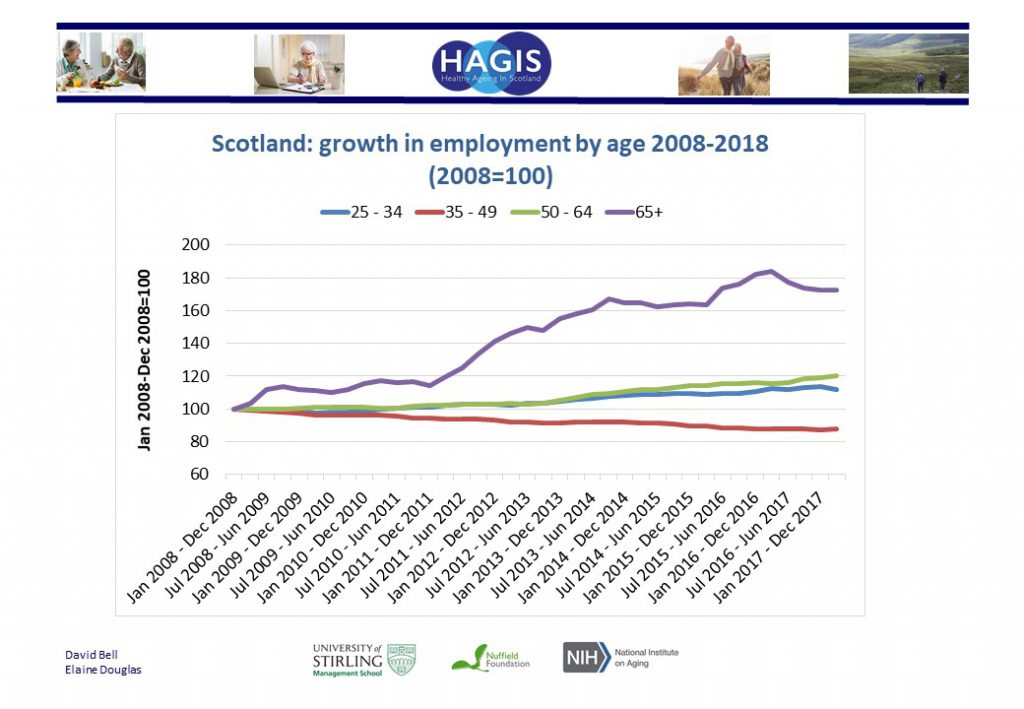

Since the recession, the growth rates for employment among different age groups have varied:

- For those aged 35 to 49, there has been virtually no change.

- For those aged 25 to 34, there has been a slight growth, although that may have been driven by immigration to some extent.

- For those aged 50 to 64, there has been a slight growth.

- For those aged 65 and over, there has been a very substantial growth in the number of people working in the labour market. The numbers are small, but the employment rate is growing more rapidly in this group than in any other.

David highlighted that there is greater inequity among those aged 65 and over, given that some are healthy enough to continue to work while others have health problems and cannot work beyond the state retirement age. That raises the issue of when the state pension kicks in, and whether people are aware of the changes to pensions in that regard. David noted that older workers work fewer hours per week, with the amount of work dropping off sharply after age 60.

“A slide that will shock you”

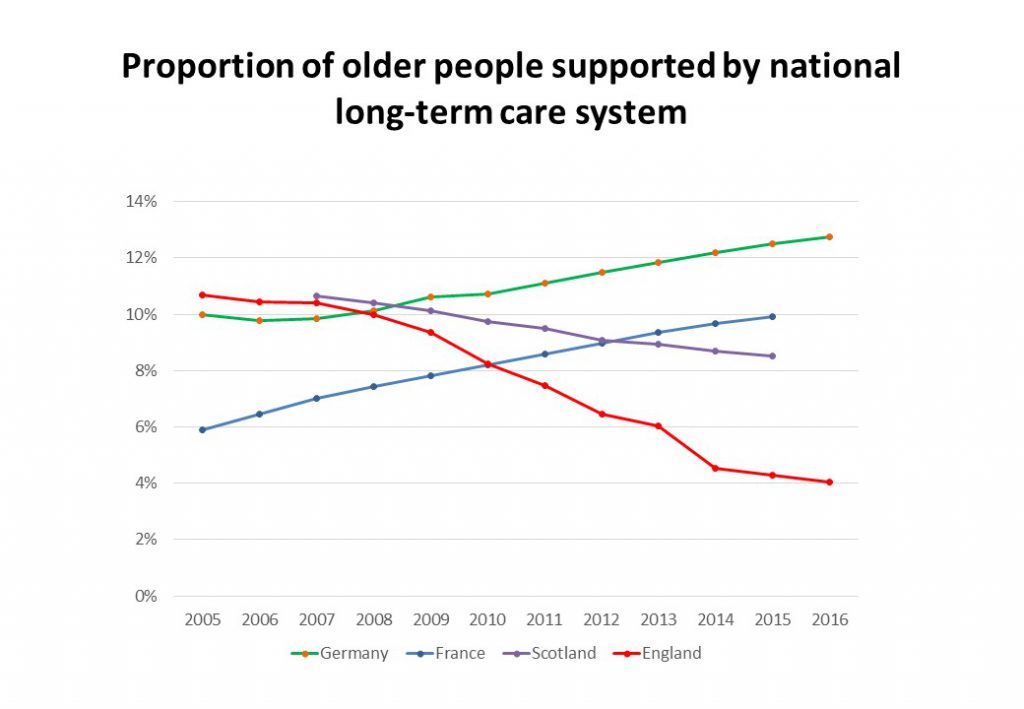

David shared a slide based on data from José-Luis Fernández of the London School of Economics, to which he had added the figures for Scotland. The graph showed the number of people who were being supported in long-term care in different countries from 2005 to 2016. In Germany and France, which have ageing populations, more people were receiving long-term care. However, the figures for England and Scotland both displayed a downward trend, with the English trajectory offering a particularly stark contrast with mainland Europe.

As David described it, that is what happens when local authority funding is squeezed until the pips squeak. He referred to a real crisis situation in long-term care funding south of the border, which is a key issue for older people.

The costs of dementia

To conclude, David highlighted another important issue: dementia. Alzheimer’s Society recently produced a report on the costs of dementia, which are substantial: around £26 billion for the UK as a whole. The charity estimates that 67,000 people in Scotland have dementia.

HAGIS is producing a detailed analysis of the prevalence and cost of dementia in Scotland. The cost is estimated at £2 billion a year—to put that in context, the Scottish health service budget is approximately £13 billion a year. It is expected that the cost will increase by a further £400 million by 2025.

Dr Elaine Douglas, Healthy Ageing in Scotland

Elaine began by placing the HAGIS study in the context of similar studies in countries throughout the world, including the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), which has been carried out every two years since 2002.

Elaine described how such studies paint a comprehensive picture of what happens to people over periods of time. That enables us to start to understand the pathways and journeys that people take and the relationship between cause and effect.

The HAGIS study asks 1,000 people aged 50 and over (increasing next time to 6,000) questions on a broad range of social, economic and health issues in order to build a fuller picture of what is going on. Those include:

- Health and social care.

- Retirement plans.

- Loneliness and social isolation.

- Wellbeing and standard of living.

Elaine pointed out that Scotland has a distinct and unique profile, which includes poor health and lower life expectancy. There are massive health inequalities in this country, leading to a much broader gap between the wealthiest and poorest than elsewhere in the UK.

With this information, cross-country comparison studies allow us to learn from other countries and compare policies. HAGIS can look at where policies diverge and where things are working well or need to be changed.

Leading the world

Elaine moved on to consider the question of how Scotland can be a world leader in the field. She emphasised that we should be proud of our administrative data system, in which the Government gathers data on health, social care, education and tax. Its positive attributes include:

- A unique identifier for everyone in Scotland, which enables detailed survey responses to be linked with NHS data at an individual level.

- The ability to follow people’s individual characteristics, along with their health service use.

- The ability to look at health service use across populations and different groups, such as smokers and non-smokers and different age groups.

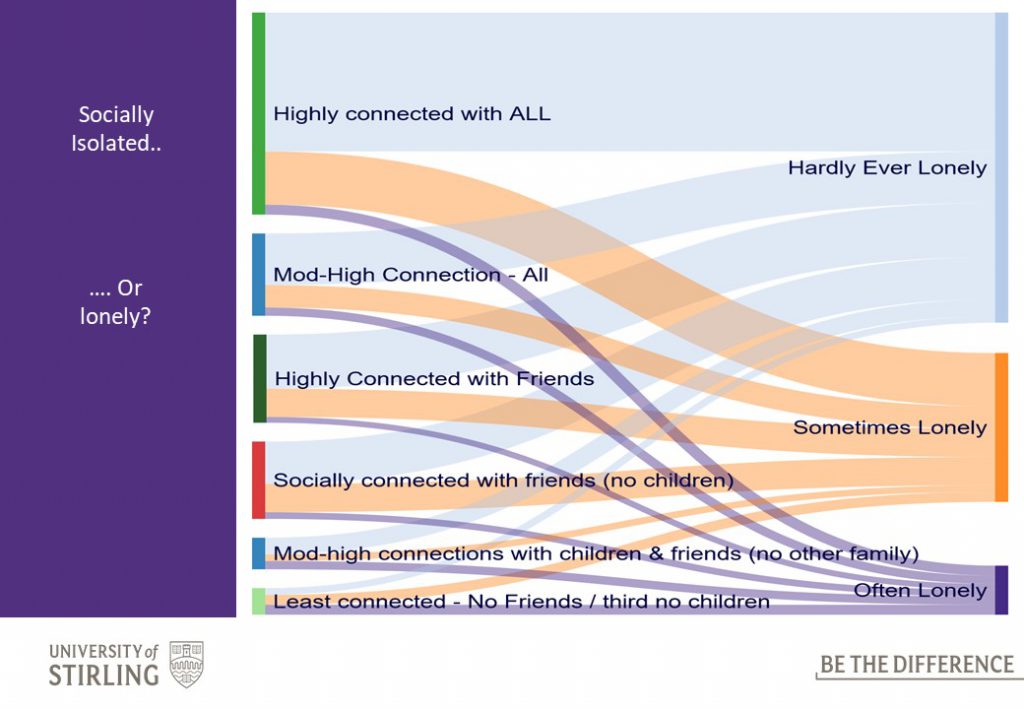

Elaine gave an example of how the HAGIS data fits into the picture. One headline issue for older people is social isolation and loneliness; those two concepts are not the same and must be examined separately. HAGIS is currently looking at the relationship between them and how they manifest in people.

Such an approach enables public health research to focus on the need for support for particular groups, because there will be different solutions for different people—a theme that was picked up in the discussion.

Discussion

At the forefront of the discussion was the issue of intergenerational tensions and the need to break down barriers. In the context of a profound shift in our economy, participants debated how society views older people and how they view themselves, linking back to the importance of good data as highlighted in the presentations. The discussion also touched on wider questions around neoliberalism and the role of the welfare state in Scotland.

An upward spiral?

The discussion began with a key question: are old people seen as an asset to society? Many older people are moving into an upward spiral and making a positive difference, but their contribution is not always recognised. It was argued that attitudes need to change so that older people are no longer viewed as a problem or burden. A tendency towards ageism was noted, including in the workplace.

Participants discussed the increasingly blurred lines between work and retirement, and the onward march of technology. Older people may be expected to engage skilfully with new IT systems rather than having the space to build on their own strengths, and some may feel that they have no alternative but to retire. However, as was pointed out, we cannot turn the clock back on technology. In the context of work, the premise of viewing human beings as assets was hotly debated. It was felt that people are often treated simply as numbers.

Are older people treated well in general? It was argued that the pensions policy is currently in chaos, and that the abolition of the state earnings related pension scheme (SERPS) has been a major step backwards for older people. It was noted that we still hear stories of those who are stuck in hospital or exploited by family members through power of attorney provisions.

Do older people see themselves as assets? It was pointed out that many are fearful of mental decline, and dementia in particular. However, as was made clear, physical decline is not inevitable and can sometimes be reversed through rehabilitation. It was argued that decline in later life is malleable and does not follow a fixed trajectory, and that a public health message to that effect is important—perhaps the Elderly Crossing street sign could feature a windsurfer or paraglider.

It was emphasised that people can live healthier lives for longer, which is important for the health of the nation as we move to 2030 and beyond. Negative expectations can easily become self-fulfilling prophecies, and it was argued that we should have higher expectations of older people.

A positive story concerned volunteering, with older people using a lifetime of skills to help others and thereby increasing their own sense of self-worth. It was noted that Dame Esther Rantzen, founder of The Silver Line, sees volunteering as a cure for loneliness. The prevalence of coffin clubs in New Zealand—where older people meet to build their own coffins—was cited as an interesting and unusual initiative. It was pointed out that voluntary work can be exploited, and that older people who want to work should be paid properly. Nevertheless, volunteering was underlined as a brilliant way to bridge intergenerational gaps and pass on learning.

Conversation as a catalyst?

There was consensus on the need to break down intergenerational barriers and improve the conduits between old and young. It was suggested that working together can build solidarity, as can friendships. People can also learn from one another through volunteering or structured learning. It was argued that there is a lack of meaningful apprenticeships, and that Scotland has not yet got to grips with policies to maximise the intergenerational transfer of experience and skills.

It is clear that tensions can be exacerbated by media narratives around generational guilt and conflict, with positive representations often limited to the cliché of nursery-school children meeting elderly folk. Participants discussed the breaking of the social contract, as highlighted by David Bell. It was suggested that discontented younger people are envious of the older generation, and there were gloomy predictions of increased hostility in the absence of huge changes.

Issues of perception were highlighted, and it was argued that a rigid differentiation between generations can simplify problems and pit people against one another. A baby boomer may feel guilty about having a good job and pension, but women in that generation often face both ways, with multiple caring responsibilities for the generations directly above and below them.

It was emphasised that intergenerational links should be about more than very young people talking to the very old. A better approach was suggested: we should build interpersonal rather than intergenerational links so that people can share their knowledge and experiences no matter what their age. It was stressed that people in general need to learn from one another, and there was a call to rebuild the community spirit of the past.

Nonetheless, it was claimed that conversation and dialogue between generations can act as a catalyst for change across society. Many positive examples of intergenerational links were cited as a template. It was suggested that, through initiatives such as Generations Working Together, people can discuss jobs and housing in order to find mutually beneficial solutions in a changing world. Conversation is valuable in challenging stereotypes and getting both younger and older people to respect and understand one other.

How do we move forward?

Dialogue is a good start, but we also need to look at policy, and education was suggested as an area for improvement. At an individual level, it was proposed that old people could be reskilled through adult education to enable them to use technologyas the nature of employment changes. It was noted that, given cuts to migration, employers must be prepared to re-educate older people, which linked back to the question of whether they are seen as an asset.

Education to improve financial literacy was highlighted as an important mechanism to ensure that older people do not fall prey to pension sharks. There was a call for drastic changes in personal and social education in schools so that young people are equipped to make decisions on pensions. The chair noted that the Parliament’s Education and Skills Committee will return to the issue of PSE soon.

Despite high expectations and some positive examples, it was made clear that systemic problems must be addressed. A running theme was the need to base solutions on solid data, and it was argued that the information from HAGIS should be used much more openly. There were fears that the Scottish Government’s forthcoming framework for older people could simply be a wish list. It was emphasised that, if the framework is to take us forward to 2030, it must be fully informed by data. There was a plea for greater information literacy so that the public are aware of how policy is developed.

It was argued that, as the issues are ultimately political, the solutions must be political too. A wider debate concerned the role of the welfare state and who should provide services, given that—as David pointed out—those in the older generation interact more with the state. The climate of neoliberalism was highlighted as an important context, although it was conceded that Scotland had done well to move to free personal care in 2001. It was argued that while the Scottish system is not without its problems, it works reasonably well in comparison with the situation elsewhere. Participants asserted that we must think for the long term, as the political cycle often gets in the way.

It is clear that Scotland has been grappling with issues such as health inequality for a long time—they are not new. It was stressed that the real problem is the complexity of those issues, which links in with the need to use data to address them. It was suggested that that would enable us to solve problems at an individual level rather than looking for sweeping solutions—given, for example, the inequalities in life expectancy across Glasgow postcodes. If we can start to look at the complexities, we can start to deliver solutions.

Overall, despite the systemic issues, it was stressed that there are many positive changes and that, if we can get a positive message out there, we will move in the right direction. To conclude, it was mentioned that, 70 years on from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, all societies, including Scotland, could do with more equality and justice.

Scotland 2030 Programme

This seminar is one of the Life in Future Scotland series run in 2018 by the Futures Forum as part of the Scotland 2030 Programme.