Leaders in Sport & Physical Activity: Shelley Kerr

On Wednesday 8 May 2019, the Head Coach of the Scotland Women’s National Team, Shelley Kerr, spoke at the Parliament in a seminar chaired by the Presiding Officer Ken Macintosh MSP.

Podcast

Listen to a podcast of Shelley’s presentation here:

Shelley spoke about how she had to battle to play football as a girl growing up in Scotland, along with the current challenges in sport and the future of women’s football.

Transcript

It is a real pleasure and an honour to be here to speak to you guys today. Normally when I’m sitting in front of an audience, I’m either letting players down or making them the happiest people on the planet. I plan to give you a quick introduction and show you a short video, and then I will present for about 15 minutes and open the floor to questions. You will have to bear with me, because I’m going to share my journey and where it all started for me. I’m approaching my 50th year—I know that’s quite hard to imagine. I hope that you can take some learnings from my journey and some of the challenges that I’ve faced along the way.

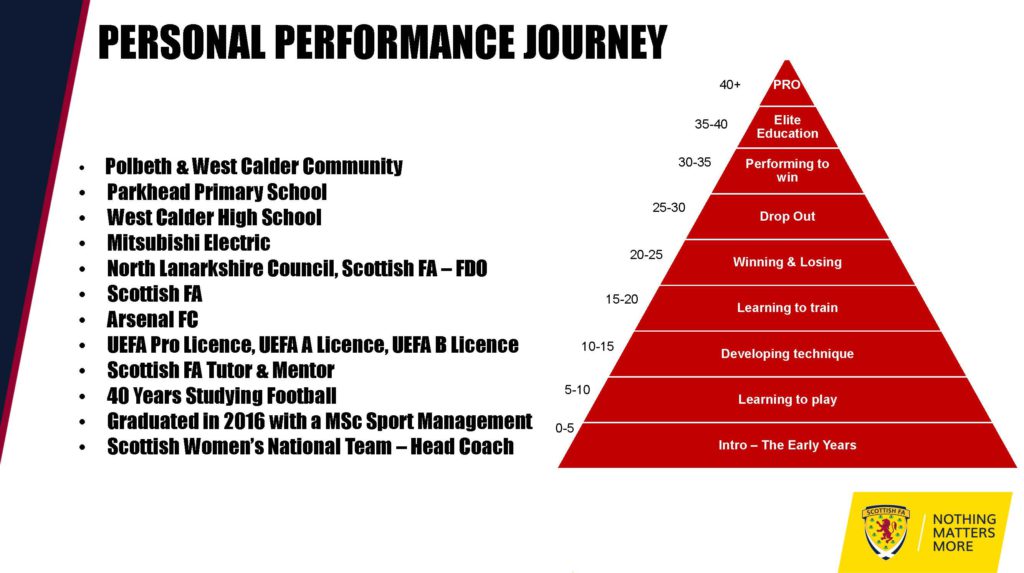

I’m going to take you back to where it all started. The first slide shows a little pyramid of my performance journey, which I want to touch on because it is important both professionally and personally. It takes a long time to develop yourself in any walk of life. On the left-hand side of the pyramid, there is a column with the age ranges going up from zero to five, five to 10 and so on. I will start at the bottom, where it all started.

From the age of about three or four years old, I started kicking a ball. I am going back 46 or 47 years to a time when, in football and in sport in general, it was deemed not the right thing to do for a girl, and especially a little girl, to play football, which was predominantly classed as a male sport.

I had two older brothers and an older sister who encouraged me to play sport. My passion was football, and that is where it all started. I played in my local village—Polbeth, a little village in West Lothian—and I played alongside the boys. Right away, there was a stigma attached to being a girl playing football; that will be a recurring theme and pattern in everything that I tell you. At the time, I probably didn’t realise it, but it started to build my character as a person and as an individual as early as three, four or five years old.

I went to Parkhead Primary and West Calder High School. From age five to 10 years, I was developing skills such as co-ordination and balance. Again, I was learning to play alongside the boys. At that time, girls’ and women’s football didn’t have any formal infrastructure, so I played with the boys. I first got selected to play for my primary team—I was the only girl—thanks to my art teacher Mr Wilkinson, who saw me playing in the playground with ripped tights and muddy shoes and invited me along for a trial.

That is really where it all started for me: my first time playing organised football. It was tough because, again, there was a stigma attached. When I turned up to play, I would hear, “That’s a girl—why is she playing football?” Way back then, that probably put a lot of females off sport in general, and especially team sports; I will touch on that a wee bit further on.

That is where I developed my technique. I played in the playground and I played on the pitch, and we developed our own games in the local village. In fact, on our local pitch, we had to make the goals diagonal so that we could make it bigger to have 20-a-side games. That was typical for many people in the era when I grew up, and it was great.

When I went to high school, I was told that I could no longer play football, which was a huge thing for me. As a young kid, it was brilliant to play for my primary school team, but when I went to secondary school they said, “You can’t play with the boys any more—you’re not allowed.” I was devastated. I pleaded with my mum, because playing football was all I was ever interested in. My mum wrote a letter to my PE teachers to ask whether I could take part in football when the girls took dancing. Thankfully, my teachers agreed to that, so I was able to take part through the school PE curriculum, but I couldn’t play for a team.

Back then, there were two leagues. It is quite hard to imagine now, when women’s football has just under 12,000 registered players, but there were probably about 200 players then. The game has evolved massively, but at that time there was no youth football for me to take part in. I couldn’t play with boys, so I ended up playing for a women’s team at 13 years old. I was playing against women twice my age.

I spent two years running up and down the touchline and not getting on the pitch, but I was so dedicated and determined that I thought I would get my chance eventually. What was in my head at that time was not negativity or disappointment—it was simply, “How can I learn from some of the senior women players?” At that point, some of them were playing national team football. I developed a lot of core fundamental skills, including life skills, from an early age. I played for the women’s team, and when I was 18 years old—to fast forward a little bit—I eventually got my first cap for Scotland, ironically against England. It was 1989, and I came on as a second-half substitute.

At that point, I had to pay £50 to represent and play for my country. I stayed in a hotel overnight when we played England. I was one of the substitutes, and they didn’t have a tracksuit for every sub, so I had the top on and someone else had the bottoms on. Again, there is a recurring theme. The reason I want to share this is because it has been important for me and where I’m at now. I’ve experienced absolutely everything: the good times, the bad times, the hard times and so on.

I left school with no formal qualifications, and it was a tough time. I was the youngest of four in the family, and it was the era of the YTS in which—correct me if I am wrong—you got around £27.50 a week for working. I was really fortunate; I was one of the lucky ones. There was an electronics company called Mitsubishi Electric that made VCRs—I am sure a lot of people in the room can’t remember VCRs. I was really fortunate as I got a full-time job with them.

I left school with no qualifications, and the job was brilliant because I earned £71 a week as opposed to £27.50 under the YTS, so there was a huge difference. My family were delighted because I’d got a full-time job, which was a struggle at that point in time—we’re talking 1985 or 1986. I have to be honest: working in the Mitsubishi Electric factory on a high-volume production line was one of the best things that I’ve ever done in my career. I started off as a production operator, and when I finished 17 years later, I was a manager responsible for three production lines and 90 employees.

Because of technology, the workforce became redundant so the factory closed. It was a new chapter for me. Working for a Japanese company taught me many things: discipline, organisation, to be efficient and effective and to manage people—that was a huge thing. There was a red category and a black category, and if people didn’t meet their targets every day, they got sacked. I’m not saying for one second that that is the right way to do things, but it gave me discipline, a work ethic and experience of managing tough situations. It doesn’t matter whether it is in sport or business: you’re managing people and dealing with human emotions. That was huge for me.

Going back to football, I had experience of playing for the national team, and I knew that I had a passion. I didn’t consider myself to be the most gifted or talented player, but I was hard-working and I had really good game awareness. I always knew that I wanted to be a coach because I wanted to help educate people.

I started to go through the coach education pathway, but in the meantime I took a break from football to have my daughter. I had eight years out—I got my first cap in 1989 and my second one in 2001. There are a lot of intelligent people in the room—I am sure you can work out the maths. To do that a second time, after being out for so long, was tough.

I went back, and I remember my coach at that time saying to me, “You’re not fit, and you don’t look healthy.” I thought, “Well, I’m not just playing at it—I’ve never played at anything in my life. If I’m going to do it, I’m going to do it well.” I took the bull by the horns, got myself fit and re-educated myself in many different ways.

I started playing football again at a really good level, and I went on to play for some big clubs. It was never about winning—it was about the experience of playing alongside different people, coaching different people and subsequently taking a new pathway in life, as I’m sure a lot of people in the room have done or will do.

I finished my stint at Mitsubishi Electric—I’m going backwards and forwards in time, so please bear with me. I’m going off on various tangents, but it is all relevant. I got an opportunity to go into the Scottish FA in a part-time position, which I took. It was never about financial remuneration—it has always been about how I can develop myself to get the skillset that I need to be successful in everything that I do. I took a chance and went into post, and then the post was made redundant. I then went to North Lanarkshire Council and worked as a football development officer.

My first coaching experience was at Kirknewton nursery school—I can tell you that it was a terrible experience for me as a coach and probably for the kids as well. I went into a very small room that was also the dining room, and we had to do an activity with the kids, who were about three or four. We used balloons and the fire alarm went off, and the kids were crying. Here I am now taking the Scottish women’s national team to the World Cup, but way back then that was part of my learning process as a coach.

An important part of my development was working as a development officer, because I started off at the very lowest end of the pathway. When you get to the top end, a lot of people think that you are quite fortunate to be working with the national team. For me, it is extremely important to have a real handle on everything to do with pathways, because that gives you real empathy and an understanding of what it takes to get through.

Not everyone will reach the top level of their sport—that is a fact. Only a small minority will do so. It is really important for me to see the development plans for individuals coming through in their sport.

I then went back into the Scottish FA—they must have thought I’d done something right the first time round. I was a technical programme development manager for women’s football. I basically looked at developing all the elite players in the pathway and devising the curriculum. I was also the under-19s manager. I will fast forward to when I went to Arsenal Ladies and made a big move down to London. Again, that helped me to equip myself to deal with players who were playing in a professional environment and getting paid.

My coaching education is extremely important, and it’s something that I’m really proud of. I knew that I wanted to work with senior adult players. In the coach education pathway, there is a children’s pathway, a youth pathway and an adult pathway. I started at the very bottom and I worked my way through all three. Eventually, in 2013, I got my UEFA pro licence.

At the top of the pyramid is the 40-plus age range. I vowed that when I delivered this presentation, I wouldn’t put in a 50-plus category—I was always going to leave it at 40-plus. The significance of that is that I’ve spent 40 years studying football. I’m not the finished article, but I do think that I’m an expert in football because of the length of time that I’ve studied in all the different areas and because of the capacities that I’ve worked in.

Besides having my daughter and getting to the World Cup, one of my proudest moments was when I graduated in 2016 with a Masters in Sports Management, after leaving school in 1985-86 with no formal qualifications at all. My pathway—my journey—has been quite different. A lot of things have been instrumental in getting me to where I am now. I wanted to share that with you, because I think it is quite important.

I had challenges as a result of my drop-out years, which a lot of teenagers in sport—especially girls—go through. Mine happened a wee bit later—I had eight years out. Things such as learning to train and play with boys and developing technique, and then performing to win, when everything goes into winning as opposed to developing, have all made up a whole host of different experiences that have been quite important for me.

If you look at the newspaper photo in the next slide, you might think that my mother didn’t like me, with that haircut. The reason I wanted to share it is that the picture is of me as a 10-year-old. I won’t read out all the text, but I was 10 years old and I had a dream of playing for my country. Dreams do come true, but it takes a lot of hard work. I wanted to represent my country, and that’s all I cared about.

It was hard back then, competing with the boys. To fast-forward, these were the headlines all those years later when I was appointed at Stirling university: “Football isn’t just a man’s game any more”,“Breaking barriers” and “Shelley is brave to be a boss in the men’s game.” I would pose one question: why? If you have the skillset and the competencies, gender goes to the side, as it should always do.

My appointment at Stirling university was a huge thing. There was a lot of media attention because I was the first in the UK. Personally, I didn’t understand what all the fuss was about, but there was a lot of fuss. The way I see it now is that I genuinely think that there will be a female manager in the professional men’s game at some point. I really hope that there will be, because there are now so many female coaches and role models who could do the job, and in years to come it should be a regular thing if they’ve got the competencies and the skillset.

I wanted to show you those pictures because, in the picture from 40 years ago and the pictures from the past few years, there are very similar messages. As much as things have evolved, there is still a long way to go in changing perceptions about girls and women in sport, especially girls playing football. I will touch on that again when we look to the future, but I wanted to share those pictures with you.

I will summarise my journey by looking at the secrets to success. For me, there are five simple points. The first is spirit and resilience. How do you develop those characteristics in yourself? I would say that I have them in abundance. I am a fix-it person: if someone asks me to do something, I always say yes, even if it’s the most daunting thing.

Number 2 and number 3 on my list are being organised and disciplined, and being efficient and effective. Working for 17 years in a factory, along with the values that my parents instilled in me, certainly epitomises those skills. They are huge in any walk of life, not just in sport. If you are organised and disciplined in life, it will stand you in good stead.

Number 4 is increased professionalism, which comes down to the education that you get, how you develop yourself as a person and how you develop leaders within a group that you work with. That is something that I really pride myself on. In the national team right now, we talk about how many leaders we have. We want to develop 23 leaders because when it comes to problem solving, which you have to do in sport because there are so many variables, you need as many leaders as possible. As much as players may be talented on the pitch, we need to help them to develop other characteristics.

The final secret to success is the team behind the team. There are so many people who are instrumental in your own development. That is true for everyone in this room: you’ve got support from family members and a support mechanism of friends around you, and you may even have mentors that other people don’t know about. It is about using other people’s experiences to help you. I always talk about the team behind the team. You are never the finished article as an individual; you need people to support you. That is so important.

In terms of my vision for women’s football, we have been successful to date, qualifying for two major tournaments: the Euros in 2017 and the World Cup. Because it has taken us so long to get the profile that we deserve, critical reflection has been a challenge. To get better at anything, you need to critique, and that is what we’ve done in the girls’ and women’s game in Scotland. We’ve done a full audit and looked at where we want to be and how we sustain our success.

The next slide shows our girls’ and women’s performance strategy. It is a twofold document that incorporates a football blueprint and looks at girls’ and women’s football from a strategic point of view. It looks at infrastructure and performance, and at how we can grow the game. That document, and everything in it, is being rolled out to all six regions in the country just now. It is an evolving document that we will look at constantly to see how we can get the best out of women’s football in Scotland.

There are four key objectives. From a performance perspective, our big objective is that we want to get to every finals. We operate in cycles and competitions, and we want to set ourselves a target of getting to every single Euro and World Cup finals. I’m not guaranteeing that that will happen, but we have been doing okay so far.

We want to provide a clear and progressive pathway into the women’s national team, especially when it comes to performance. That involves looking at all the youth teams. I’ve mentioned the need for critical evaluation and reflection. We need to be proactive in identifying the best teams and players on the world stage and the European stage.

The last objective, which is hugely important, is about how we professionalise the game in Scotland. People can misinterpret the word “professional”—they think that it’s about getting paid to do something, and that’s not the case. It is about taking a professional approach, which we are very much looking at in the domestic game in Scotland. As you’re probably aware, the majority of our national team players are playing outwith Scotland. We’ve got a duty to make sure that our domestic product is good as well, and that we get resources into our domestic league.

Moving on to the next slide, how do we make the World Cup a platform for success? There are two parts to that. First, there is the performance side. The target is for us to get out of the group stage—we know that it will be tough, but that is our target. I will readdress that target if and when we get out of the group.

The second point is that we’re going to the World Cup for the very first time, and to ensure that it happens again we need to make sure that we grow the game. What does that look like? We are looking at how we support the best players in the country. Can we provide them with a professional environment so that they can improve? Can we provide an environment that means that they don’t leave to play in other countries, so that we get a better product in the domestic game?

Can we offer scholarships? In the current pathway, we have the under-15s, under-16s and under-17s, and then the A-squad. There is too big a gap—we need an under-21s or under-23s team in there, but at the moment we don’t have the resources for that.

There is a whole host of things that we need to do. The biggest one is inspiring the country: as a national team, we have a duty to captivate the nation. With success comes a greater profile, along with more marketing and sponsorship opportunities. We hope that we can grow the game, because we don’t want the two times that we’ve qualified for major tournaments to be isolated cases. We need to make sure that we reinvest in the women’s game. That is a big thing, not only for me as the national team coach but for the players as well. They are real role models and they want to make a difference for the future. That is hugely important for us.

Moving on, I will offer some personal views on the long-term future for women’s participation in sport. Nowadays, as you can see from the slide, we have Judy Murray, Katherine Grainger, Elise Christie and Laura Muir. When I was a kid, I wasn’t exposed to role models. That is a huge element. These days, I could have picked out numerous female role models when I was putting the slide together. That is important if we want to inspire young girls to get involved in sport. It is not about performance—it is just about participation; girls need to have a good visual and they need role models they can look up to. Whether they go on to play at a performance level or just recreationally, that is so important.

The more we see those role models, and the more we know their names, the better it is for our young kids from a physical health and wellbeing perspective. How can that happen? We need to build a system for women in sport. We need to look at resources: time, investment, expertise and information. We need to look at the enablers: the places, the people and the profile. We also need to consider the environment. Facilities are hugely important, as are building relationships and the programmes and pathways for young kids. Those need to be cohesive, and we need pathways that cater for everyone, not just the elite.

Everyone—even the players in the national team, and me—starts off by kicking a ball about in a park. That is where everyone starts, whatever sport they do. You play the sport because you enjoy it and you want to have fun. It is important that we get the right pathways and programmes in place to cater for absolutely everyone.

We also need to look at outcomes. Not everyone is going to be a top performer—it is also about education, qualifications and professionalism. How do we retain people in the game? Who are our next physios, administrators and so on? There are so many opportunities in sport. How do we get more volunteers involved? Volunteering is a huge area. We also need to consider equalities and inclusion, and people’s development. How do we develop people’s skills and take a collaborative approach? That aspect is huge.

We have a genuine duty to make sure our kids are physically active in the early years, as that is a huge problem. We’re going to the World Cup, but in years to come, if we’re not careful, we won’t have any sports teams going to major tournaments. It’s been 20 years since a football team from Scotland has been at the World Cup.

From a health perspective, we need to ensure that we put in the right resources during the early years to develop the fundamental core skills for physical wellbeing. I see a big change in society: our kids aren’t as fit as they once were. As a collective, we need to explore all the answers and put them in at an early age—even more so with females, because so many females drop out of sport. Speaking from experience, I found that being out of football for eight years and then coming back was tough. We need to make sport as accessible as we can.

That is me finished—apologies for going off on a tangent. It’s probably not the structure that you would normally have, but I was really keen on sharing my journey from both a professional and personal perspective. You need all those experiences in life to get to where you want to be. It’s never a smooth journey, and I don’t expect that it will be a smooth journey in years to come either—there’s no doubt about that. I’m eager and keen to hear any questions that you might have—thanks for listening.

Slides

Q&A Session

The Q&A session ranged widely, bringing in Shelley’s clear belief that support for sport and physical activity in the early years is vital in building a healthy nation.

This seminar was part of a series from Leaders in Sport and Physical Activity. Information about all the seminars is available on the Leaders in Sport and Physical Activity Seminar Series page.