Finnish Lessons: Olli-Pekka Heinonen

Wednesday 4 March 2020, at the Scottish Parliament

In conjunction with the David Hume Institute, Scotland’s Futures Forum held a seminar in March 2020 with Olli-Pekka Heinonen, the Director General at the Finnish National Agency for Education.

Olli-Pekka spoke about the Finnish approach to education and how it is preparing its people to meet the challenges of the coming decade.

The event was chaired by Clare Adamson MSP, Convener of the Scottish Parliament’s Education and Skills Committee.

Podcast

Slides

Presentation Transcript

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to talk about some of our experiences in the Finnish education system. I would like to share some of the main principles as well as the challenges that we face and how we are trying to tackle them.

I have really enjoyed being here—I am a regular visitor to Edinburgh, and it is so nice to be here. My last time in Scotland to discuss education issues was more than 20 years ago—I was in Inverness, where I spoke to the rectors of the universities about how small nations approach autonomy for universities and how national decision-making happens.

I will start with some lessons and the basic fundamentals of education in Finland. There are a lot of similarities between Scotland and Finland when it comes to population. We have two official languages, Finnish and Swedish, and the Swedish-speaking minority makes up around 5% of our population. At the moment, around 6% of people who live in Finland have a foreign background.

Quite often, when we look at international comparisons, there are three areas in which Finland seems to be doing well.

- In respect of equal societies, we are quite near the top of the list in gender equality and other aspects of equality.

- The same applies when we talk about the stability of nations: Finland has been ranked as the safest and most stable state.

- The third area is education and innovation.

It is important to understand that those three areas in which we are doing well are strongly interconnected—they feed into each other very strongly in Finnish society.

No matter which school a parent decides to send their children to, their closest school will be a good school, and that is something that we try to maintain.

Education-wise, the idea of equality has been our strength. We do well in PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment), for example, not because we have the best pupils in terms of achievements; our strength is that all our pupils are doing quite well.

The differences between schools in Finland are the smallest among the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries. No matter which school a parent decides to send their children to, their closest school will be a good school, and that is something that we try to maintain.

Equality and a good level of education feed into the stability of our society. There are not strong contradictions between different groups; the social capital of our society is a big thing in Finland.

The thing that connects those three areas is trust, which explains a lot about Finnish society. There is a lot of trust in our society, and trust is a central pillar of our education policy.

- The Finnish education system is a network of autonomous actors. The teachers, who have a master’s-level education, have a lot of autonomy in pedagogy and in how they reach the learning and teaching outcomes at a national level.

- The schools have a lot of autonomy too, and they are run mostly by the municipalities, which are autonomous under the constitution.

- Teacher training happens in universities, which are of course autonomous.

It is a network of autonomous actors, and there needs to be a lot of trust between those actors in order for things to function well. I will come back to that point when I talk about the challenges.

The Finnish constitution states that equity is the starting point for our education, and that idea has long historical roots. When Finland first decided around 170 years ago that it wanted to be a nation among nations, there was an idea that the best way to do that was to raise the educational level of the whole population in our own languages and culture. Education was seen as a means to achieve the status of a nation, and that has carried on throughout the centuries.

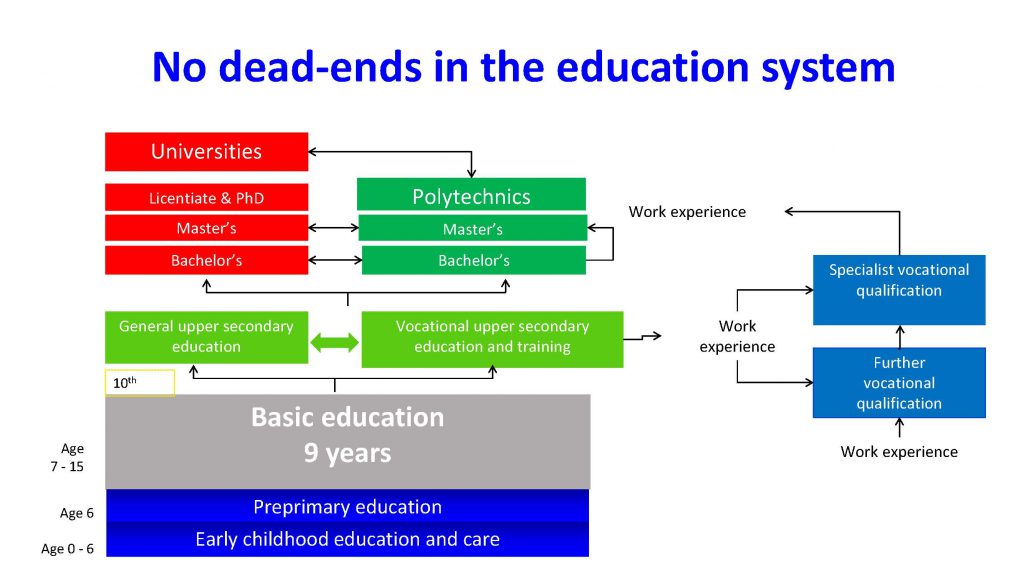

In talking about equity, it is very important that we create our education system so that there are no dead ends. No matter what choices a child or young person, or an adult, makes, there is always the possibility that they can make other choices. They do not end up making choices that mean that they cannot write a doctoral thesis or whatever later on.

As I said, trust runs through the whole system. We made some big reforms in Finland during the years 1991 to 1997, when we reformed the whole education legislation.

We had previously decided in 1972 that teaching and educational qualifications would be master’s-level qualifications. Once the generation of teachers with that educational background were in post, they started asking us to give them more freedom and autonomy to teach, so that is what we did. We increased the room for manoeuvre for teachers at a local level.

Trust goes all the way down to the pupil and the student. The teachers trust their pupils and students, which is very important because the idea of continuous evaluation—the feedback loop between the teacher and the pupil—is vital in the Finnish system.

The idea is to understand what a child already knows and what he or she does not know. If there is no trust between the teacher and the pupil, the pupil will not say, “I don’t understand this.” When the trust is there, there is an understanding that the teacher is trying to help the pupil, so they will say if they do not understand something. There is then the possibility for a learning evaluation loop to happen.

Education in Finland is developed strongly in partnership. We are a small nation, which gives us the possibility of gathering all actors together—that is very typical in the field of education. When we are thinking about whether there are certain challenges that we should tackle, we gather all the stakeholders together, and we start looking at what we can do together.

There is then a process of trying to find solutions. That makes things easier once the decisions are made in Parliament: all the important actors already know about the content of the reforms and why they have been made, so the implementation process becomes much easier.

We definitely have many challenges in Finnish society. A lot of them have in common the idea that, in education and training, we still believe that we know beforehand what the learner should know. We give them something that somebody already knows but they don’t, and after their education and training, they know it too.

That is an important part of education—it is about transferring everything that human culture has been able to create so far in different disciplines, knowledge bases and so on. But it is only part of the job.

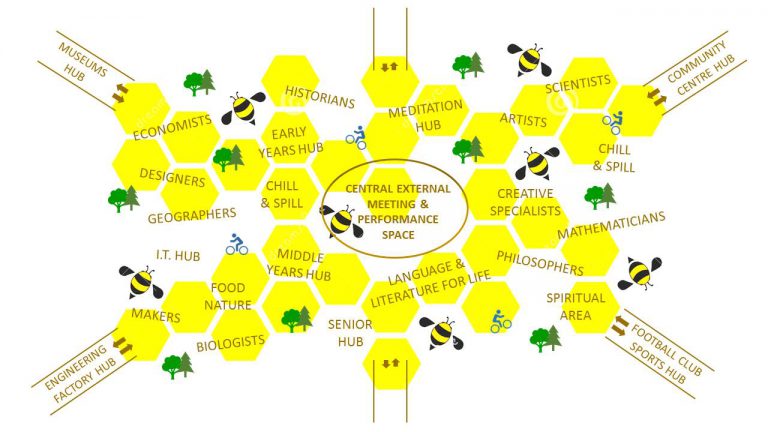

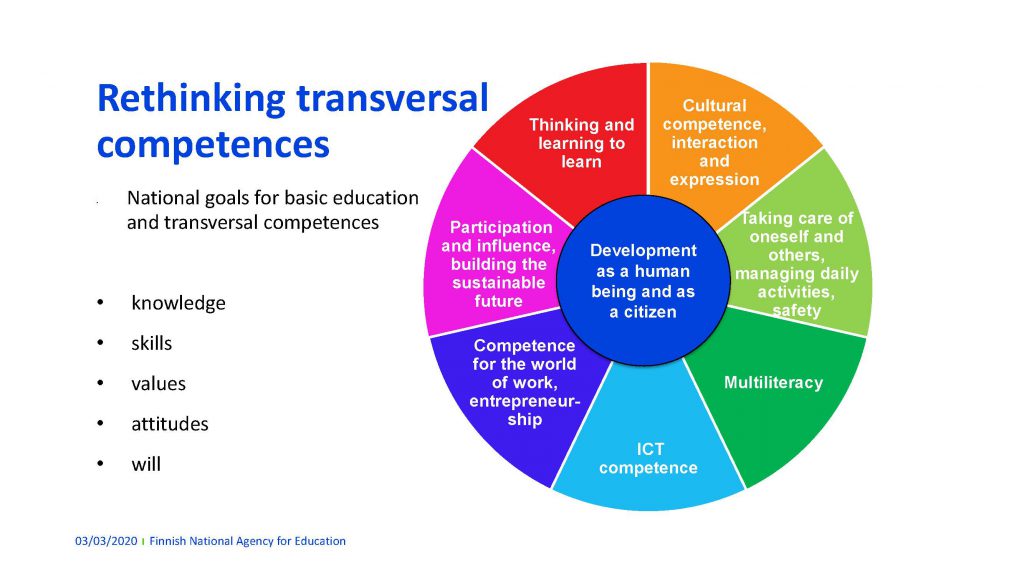

There is also the question of how we equip children for a future that is complex, and which we cannot predict. That is something that we have tackled in the national core curriculum for Finland. We still have the basic subjects such as maths, history and biology in our schools, but we put a stronger emphasis on transversal competencies, which have a lot in common with the idea of 21st century skills.

What is important in the Finnish education system is that the aim of all education in Finland is to educate the whole person: not just to give people qualifications to enter the labour market, but to see education as a more holistic challenge.

The aim is to help each child to grow into humanity, to be a responsible member of society and to have the skills and knowledge that are needed in life. That is what the legislation in Finland says about the role of our basic education.

In that way, we try not only to emphasise knowledge and skills, but to combine those things with competencies. It is not only about what you know and what you are able to master in that sense, but about what you can do with what you know. That idea is central in our new core curriculum.

I turn to some of the challenges that we are trying to tackle. First, the needs of children when they come to school are more diverse today than they were 10 years ago, and schools and teachers are struggling a bit with how to cope with that diversity. There are many reasons for why needs are more diverse, so I will not go deeper into that.

In looking at how we maintain a coherent educational policy in a situation where there is a lot of autonomy, we see that the only possibility is to strengthen the learning culture in schools and educational institutions so that they themselves can tackle challenges.

Too often, when there is a problem in one school, it is on the desk of the minister for education the next day. There is nothing between those levels, and the school itself cannot solve those kinds of problems. We are trying to accomplish a change so that schools and educational institutions have the strength, through their own capacity and resilience, to solve those everyday problems.

The leadership in the system then becomes very important. In Finland, we have the pleasure of knowing that there is a very strong consensus on education issues among our political parties, which has made long-term development of the education system possible. When the Government has changed, we have not moved from one way of making policy to a different way of doing things. We want to carry on in the future with that long-term development approach.

In Finland, there is a very strong consensus on education issues among our political parties, which has made long-term development of the education system possible.

As I said, there is more diversity in in the starting points of students and pupils, and in their needs. There is still an idea that we educate people by giving everybody the same: they start school at the same age and, when that class is finished, everybody moves to the next class, and everybody starts from the same line.

That is not true in Finland. When we look at learning outcomes, there may be five-year differences between children in the same class, and we still pretend that they do not exist, when that is not true.

To achieve equity and equality, we have to diversify and personalise the learning path to take into consideration the needs of each child. The question of how to do that is a huge challenge for teachers. Of course, there are certain possibilities that relate to new technology and how it can help with personalised learning paths.

We in Finland are proud of the fact that our schools combine good learning outcomes and a feeling of wellbeing among pupils and students. Those both happen at the same time. As is sometimes discussed, wellbeing is a problem for the Asian nations that do well in PISA. We see that we have to take care of both those areas at the same time. If the wellbeing is not there, the learning will not be there. When they are both there, it means that we can create the ability for an individual to take care of his or her wellbeing in the future in a better way.

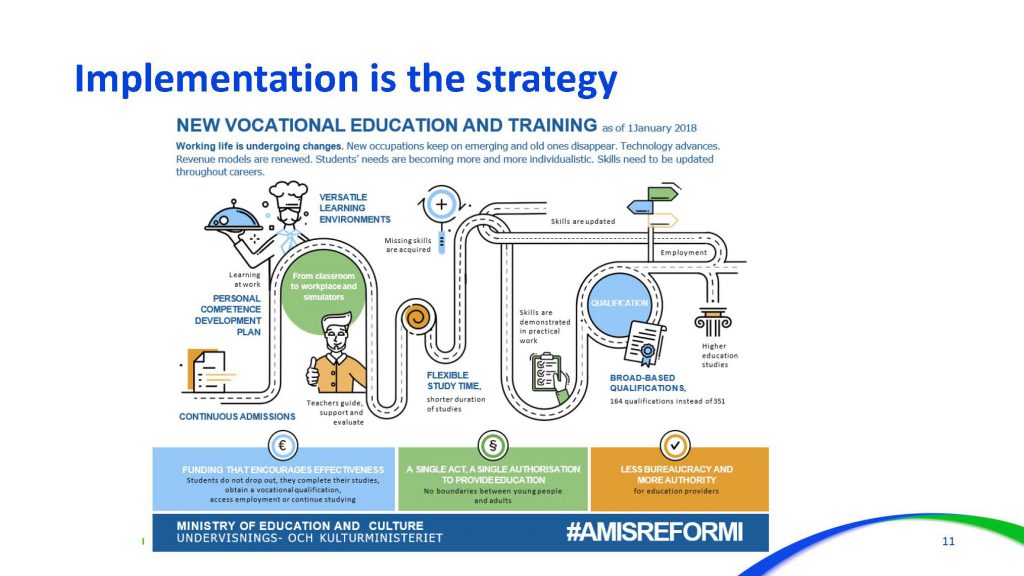

Vocational education is one area where we have been able to make personal learning paths possible. A recent reform in Finland has made the whole system competence-based. The idea is that when a student comes in, whether he or she is a young person or an adult, we first look at what they already know, and then we concentrate only on the areas that are missing.

We do so in a way that takes into consideration the person’s abilities to learn on the job, and whether he or she needs more support through a different type of learning—for example, in a vocational education institute where teachers are strongly involved.

Lastly, we are trying to move away from the educational system approach to a learning system approach. What becomes important then is not only the formal education that educational institutions supply; there is also a question of informal learning and how we make that visible, and how we can build the human capital of each individual. That approach brings the labour market, with learning from labour organisations, and the education sector into close dialogue with each other.

Speaker biography

Olli-Pekka Heinonen is the Director General at the Finnish National Agency for Education and a former Minister of Education for Finland.

Before joining the Prime Minister’s Office in March 2012, he worked for 10 years as a Director in the Finnish Broadcasting Company.

Before that he had an active career in politics between 1994 and 2002, serving as Minister of Transport and Communications from 1999 to 2002, as Minister of Education from 1994 to 1999 and as Member of the Parliament of Finland from 1995 to 2002.

Partners

The David Hume Institute is an independent think tank, committed to objective, evidence-based research and analysis on some of Scotland’s most pressing challenges.