Equity and Scottish Education

2 September 2015, at the Scottish Parliament

If we look over the horizon to 2020, what would an equitable education look like? This Goodison Group in Scotland forum, hosted by Scotland’s Futures Forum, focused on equity in education and improving attainment.

Background

The Scottish Attainment Challenge was launched in February 2015 to improve educational attainment in Scotland’s most disadvantaged communities. The Challenge is underpinned by £100 million in funding over four years.

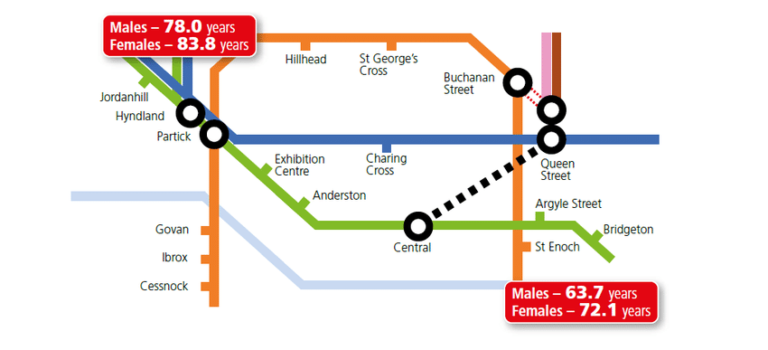

The Challenge was launched to respond to inequity in Scottish education. Although there was a similar spread in the abilities of Scottish children, outcomes varied significantly across the social spectrum. Children with additional support needs, low attendance and/or who weresocially disadvantaged wereleast likely to reach their potential. Inequity exists across life courses and transitions; negatively impacting early years education, school attainment, post school life chances and health outcomes.

In early 2015, the Education and Culture Committee undertook work on the educational attainment gap. To date the focus of this work has been:

- The implications for schools, teachers, and pupils of the Commission for Developing Scotland’s Young Workforce (the ‘Wood report’).

- How parents and guardians can work with schools to raise all pupils’ attainment, particularly those whose attainment is lowest.

- The role of the third sector and the private sector in improving the attainment and achievement of all school pupils, particularly those whose attainment is lowest.

Later this year, the Committee will take evidence from the Scottish Government and local authorities on the outcomes achieved by their efforts to improve attainment. The Goodison Group in Scotland (GGiS) has been given the opportunity to contribute to this work and will meet the Committee later this year.

Introduction

In line with our aims and objectives to influence thinking on future policy and practice, this GGiS discussion focused on equity in education and improving attainment by framing the session around the following challenge statement and questions:

- Education in Scotland is good, however to be truly great it needs to be more equitable.

- If we look over the horizon to 2020, what would an equitable education look like?

- What policies, practices and initiatives are currently helping to achieve this vision of an equitable education?

- What are the challenges and barriers to implementing significant change to achieve this vision of an equitable education?

Speakers

Our debate was informed by an excellent presentation from Craig Munro, Executive Director of Education and Children’s Services in Fife Council.

Risks/barriers to achieving educational equity

Both the Standards in School’s Act 2000 and the Wood report define educational equity as enabling young people to develop their personal potential to the full. The ability of Scotland’s children follows a normal distribution, however not all of our children are reaching their potential. Why not?

Policy

Although equity in education is a critical part of the agenda, we need to make sure we focus on the challenge of ensuring our education system is relevant for the world all our children will live in, not just one element or concern. On paper we seem to have all the bits of the jigsaw however we need a compelling narrative to allow people to see one, aligned agenda. Nationally, we may be on the cusp of something special however if we do not demonstrate how the elements/work streams come together, there is a risk we will lose the progress we have made over the last few years.

Austerity

The wider economic and social context within Scotland exacerbates inequity. The May 2015 OECD report ‘In It Together’, highlighted that the UK has the 6th greatest income inequity in the OECD. ‘Austerity’ is here to stay for the foreseeable future. UK public sector spending is being cut, putting increasing pressure on the delivery of public services.

Communities are also impacted by austerity. Children growing up in middle income communities are surrounded by role models who have completed further education and have successful careers. More often than not, they are supported by parents who take an interest in their education and apply a degree of pressure and expectation regarding their educational progress. Children growing up in deprived economic areas may lack role models to aspire to and their parents are often unable to provide the right support.

Children in low income families also have unequal access to educational opportunities e.g. they may not have access to technology at home to support their studies, they may not be able to participate in paid for extracurricular activities and their parents may be unable or unwilling to fund further education.

Demographic change

Our population is ageing and child poverty is increasing. There is also a growing expectation of and reliance on our public sector. Changes to family composition can mean that the state is expected to provide for individuals that would once have been cared for by their families. There is a greater demand for public sector resources at a time when supply is being reduced.

Politics

Education in Scotland is becoming increasingly politicised. Politicians make statements and promises that are often a distraction or focus on inputs rather than outcomes. Cutting class sizes is a good example. There is no empirical evidence that smaller classes automatically result in better educational outcomes; the quality of the teaching is a more significant variable than the size of the class. However it is a popular policy that resonates with parents. The nature of the election cycle can also lead to short term thinking and policy boredom. Sound ideas are often not given enough time to bed down or are overtaken by new initiatives.

The degree and pace of change in education is also impacting the relationship between teachers and the state.

Availability of opportunity

There were mixed views over whether there is a mismatch between educational and employer expectations of attainment and availability of opportunity. Decades of emphasis on the importance of attending university and achieving a degree may have resulted in an overqualified workforce without the necessary jobs to satisfy demand.

However this did raise the question, are we clear about what we mean by attainment at each stage of progression?

From a school’s perspective, the implementation of the Curriculum for Excellence and the recommendations from Developing Scotland’s Young Force (Wood) and Teaching Scotland’s Future (Donaldson) have changed our understanding of desirable attainment and achievement. In addition to numeracy and literacy and success in qualifications, both wider achievement and employability skills are seen as important outcomes of school education. Local authorities and schools are looking at the extent to which the system can be flexible to the needs of industry.

This discussion again emphasised that it is not the direction of travel that is the issue but how quickly education can implement and deliver.

People Factors

The professionalism of teachers, in essence their professional knowledge, technical skills and focus on pupils as individuals, has the greatest impact on educational attainment. Good teachers achieve good results for their pupils. Yet, teaching skills vary enormously and there is a shortage of good teachers. Many schools in areas of low income and child poverty find it difficult to attract and retain the best teachers, exacerbating low educational attainment. How do we match the best talent to the toughest challenges?

There is also emerging evidence that unconscious bias can impact educational outcomes. Knowing that a child is from a low income or problem family may unintentionally influence teacher behaviour. Teachers may expect – and crucially, accept – lower levels of attainment from this demographic than children from other backgrounds.

System complexity and scale

Education is delivered within and impacted by a complex system of stakeholders and providers. It is generally accepted that Scotland has an appropriate mix of policies to address the key challenges and to enable its national outcomes to be achieved. Collectively, Curriculum for Excellence, the focus on early years, and GIRFEC, together with Christie, Donaldson and Wood provide a coherent framework to tackle inequality in Scottish Society. There is, to a significant degree, a shared common purpose and consensus regarding outcomes. It is the implementation of policy that may present the biggest challenge nationally. One contributor suggested there was misalignment of National Government policy – down the different pillars of central government – with delivery on the ground, particularly to Education and Children’s Services in local Government.

Strategies can be fragmented and delivered on a project-by-project basis leading, at times, to what was described as “projectitus.” Each layer of the system may be structured differently and have different roles and responsibilities, which can make interaction and communication difficult. As an example, a Head Teacher may be simultaneously dealing with several projects that impact their school, each being managed in isolation by separate teams, tackling different components of the same problem.

Engaging parents, carers and the wider community

There were mixed views and experiences regarding schools working in partnership with parents/carers and the wider community. Some schools do this extremely well however the experience of some parents/grandparents was less positive. There is a huge opportunity to take advantage of ‘parent capital.’ One Forum member asked, which few changes/additions to primary school premises would make them more parent friendly? What would be the cost? How might these be funded, possibly from the National Lottery or through local partnerships? Could we draw a picture of half a dozen such changes to inspire communities to act and show them how funding might work?

We also need to understand how education can best collaborate with youth workers and agencies/organisations that support young people in areas where parent/carer aspirations for their children may be lower and engagement with schools is limited.

Putting the school at the heart of the community was a key policy in the mid 90’s with the implementation of full service community schools. However we seem to have moved on; perhaps another example of policy boredom?

Opportunities to improve educational attainment in Scotland

Despite the difficulties highlighted in this report, it is far from doom and gloom in the Scottish education system. There are already some great examples of policies, practices and initiatives that are demonstrably helping to achieve Scotland’s vision of an equitable education. Learning from these examples and extending best practice across the education system would go a long way to closing the attainment gap.

Evidence based approach

There is a large body of research outlining educational practices that deliver better outcomes. Unfortunately, the research is not as widely known as it should be across the broader educational ecosystem and it is inconsistently applied. We should challenge policy and practice more if the evidence – and our experience – does not support it. As an example, schools are encouraged to widen subject choice however recent research (Iannelli, 2015)1 suggests there is a link between widening subject matter choice within a school and inequalities in entering higher education.

However, whilst an evidence based approach is to be commended, some things cannot be quantified; we’re dealing with a human system not a clockwork one. We should also be wary of the creation of a culture that will only implement tried and tested ideas. We need to be able to create and innovate too.

1 Iannelli, C & Klein, M; 2015, ‘Subject choice and inequalities in access to higher education’, University of Edinburgh.

Early Intervention

Whilst OECD evidence points to the ineffectiveness of separating young people out, a targeted approach to the delivery of education has been successful, for example improving literacy in Fife schools. These schools target resources to those that need it most i.e. delivering solutions which are universal (all pupils), focused (supporting the needs of specific pupil segments) and targeted (supporting the needs of individual children).

Action research focused on improving early literacy and communication within vulnerable families has also had impressive results. Improving parenting and attachment has been an essential component of this work.

Integration and engagement of all stakeholders

Experience tells us that taking a holistic approach to service delivery – integrating education and social work – may be difficult culturally and organisationally but can be effective if done well. There are already some excellent examples of close, collaborative working, integrating professional services to best effect.

We also need to trust and support schools and teachers more. If a child fails, schools are often blamed, yet schools are only one component of a complex educational and societal ecosystem. One forum member commented that we do not blame the local medical community for the poor health of the neighbourhood yet we often blithely apply the same simplistic thinking to educational attainment.

Global versus local

There is a natural tension between the national educational policy framework and system at a country level, and the local needs and variation to be found at a school/community level. National coherence and integration is important but we also need to enable local implementation and decision making. We need to devolve real decision-making to schools and teachers – whilst accepting that this is messy – and enable them to exercise freedom within a framework.

The key to successful integration is likely to be behavioural rather than structural. Strong communication, partnership and collaboration skills of all stakeholders are essential to enable the educational ecosystem to function at its best.

Embracing a more diverse and inclusive definition of attainment

Attainment in educational terms is often narrowly focused on the accumulation of qualifications and can lead to the creation of somewhat simplistic school league tables. It is vital that we adopt a more outcomes-focused approach: measuring what matters, benchmarking intelligently, and giving due weight to the child’s voice.

It is proposed that we should take a more rounded and balanced view of achievement by children and young people. We must recognise a more rounded view of a child’s development, including:

- The development of key skills like literacy and numeracy.

- The development of employability and life skills (e.g. communication & personal skills).

- Evidence of achievement that will equip young people for a wide range of opportunities and that will enable improved life chances.

- A holistic sense of the child’s wellbeing (including the child’s ambition, self-confidence, physical and mental health, safety, responsibility, etc).

- The child’s own perceptions.

We must also present a more rounded view of school performance, reflecting each child’s individual potential, including:

- Benchmarking against social context (to allow for differences in outcomes at a cohort level that are due to the school’s social context).

- Benchmarking against the prior attainment of each child (to avoid limiting our ambition for any child on account of their social context).

As a practical example, the Children’s University recognises a wide range of reflective learning activities in terms of educational attainment.

We should also value diversity in our schools. The 1984 publication, Education for Democracy summarises this perfectly. “Beware a narrow view of attainment in terms of qualifications; the middle class view is not the only way. Education systems often exclude parents – and children – who do not fit the mould.”

We also need to remember that attainment does not stop at the end of the formal education system. We need to consider learning throughout life and access to broader learning opportunities

Professionalism of the teaching community

The available data shows that the quality of teachers has the greatest impact on educational attainment. Good teachers deliver good results. We need to develop teachers and equip them to teach well at every stage of their training and onward career.

A strong, evidence based teacher training should be supplemented by an ongoing commitment to professional development. We need to give our teachers the space and time to reflect and practice. We should expect our teaching staff to be continuously learning from research and from colleagues and sharing best practice.

Engaging, involving and educating parents and carers

There are some great examples of schools working in partnership with parents, carers and the local community. As an example, some schools are teaching parents adult literacy alongside their children. Literacy improves in both parent and child as parents are more able to support their children.

Engaging end users meaningfully

Increasingly, schools are being asked to consider the services they offer from an end user perspective. There are some great examples of schools engaging with and listening to learners, both from within their schools and the wider community. Engagement enables schools to provide a greater service offering and customer experience. Meaningful engagement necessitates the devolvement of power – if you ask, you must listen and act.

Education delivery models

Retain the current education delivery model. This approach has the benefit of ensuring stability however it is unlikely to deliver further progress in closing the attainment gap, particularly against a background of austerity and reduced public spending.

Status Quo

Retain the current education delivery model. This approach has the benefit of ensuring stability however it is unlikely to deliver further progress in closing the attainment gap, particularly against a background of austerity and reduced public spending.

Shared service/regional models

This model shares service provision on a regional basis, potentially reducing costs and enabling centres of excellence to be developed. This model is potentially enabled by technology and distance learning however it requires further clarity in respect of governance and leadership.

Maximum Delegation

In this model, we see maximum funding and decision making devolved to individual schools/Head Teachers. It enables education to be delivered in a local context however it is unclear whether the most disadvantaged would be any better served or safeguarded.

Minimum Delegation

A centralist/global approach to education delivery ensures that overall purpose and vision is protected however one size rarely fits all and this approach is swimming against history.

Trusts

Educational trusts may result in savings and protect services; however the role of other stakeholders, including local authorities, would need to be clearly defined.

Outsource

To some extent, education is already outsourced by virtue of the private school sector. Should this be extended? Would the power and virtue of the market prevail? In reality, who would protect the most disadvantaged and is this really the Scottish way?

Cocktail

Is the most pragmatic approach to adopt elements of each delivery model or would this just result in a system that was too complex? Are we afraid of making a decision?

Conclusion and Recommendations

It was becoming clear from the discussion that we had a great opportunity – along with some challenges – to make further significant improvements to the equality in education agenda by 2020.

There was general consensus that educational and social policies were, in the main, sound with shared common purpose and outcomes. The issue and challenges lie with the implementation of these policies, particularly the lack of cohesion at both a national and local level.

A lot of good and important work is taking place and there are examples of local authorities that can demonstrate significant improvements in educational practice and attainment.

However, it was also recognised this is both a generational and cultural issue and there is a need to look beyond 2020, to a 2nd and 3rd Horizon. The Goodison Group in Scotland and Scotland’s Futures Forum are well placed to contribute to this type of future thinking.

In addition to developing thinking beyond 2020, there were a number of more immediate term enablers and ideas identified during the debate to be explored further and discussed with the Education and Culture Committee.

Strategic Narrative

The need to develop a compelling narrative, which promotes one agenda in relation to the education of our children, the policies that provide the bedrock and explains how all the elements fit and work together.

Delivery Models

Is there an opportunity to consider alternative education delivery models/structures that will not only provide a more equitable education, but will improve education across the board? Or is structural change to be avoided as it soaks up energy and can divert focus from learning and teaching? Collaborative mind-sets and behaviours can do much to overcome structural challenges.

Best people in hardest shifts

The challenges and implications of encouraging the best teachers to take the ‘toughest shifts. The national pay framework makes it difficult to incentivise teachers to work in schools with low attainment levels. Should we be able to differentiate remuneration so that we can attract the best teachers to those schools that need them most?

Leadership

Traditionally, teachers progress through a school’s organisational hierarchy, ultimately emerging as Head Teachers. As our schools become more complex organisations, increasingly crossing community boundaries, do we need to rethink the leadership of our schools? It is likely we will need fewer leaders who are capable of leading more complex organisations and/or a broader concept of distributed leadership. What is the right mix of skills and experience that they need to be equipped with? How will we recruit and develop them?

Building teacher professionalism

If the skills of teachers have the greatest impact on educational attainment, logically, we need to increase their professionalism and skills. To do this, we need to create the time and spaces to enable teachers to focus on continued professional development. We need to make it easy for teachers to access best practice research and share ideas e.g. through the creation of knowledge hubs.

Evidence based approach

It is not enough for teachers to be aware of best practice in education and evidence based research. We need to share evidence with all stakeholders across the educational ecosystem to ensure we make informed decisions at every stage of the educational process.

Engaging the wider community

What is our message in the best of language to parents to compel them to gain an interest in the prospects of their next generation? Have we truly exhausted the best ways of engagement and if not what can be done to bring about a change of culture? Whilst there are some examples of schools engaging parents and carers, this is not consistent and more could be done to engage communities, enabling them to fulfil a deeper commitment to the wellbeing of Scotland’s children and to have greater ownership of outcomes.

Other ideas mooted during the forum included educating parents and carers on the learning process and curriculum so that they helped – rather than hindered – their children’s education e.g. understanding how a child learns to read.

Finally, a note of caution

Equity is significant but it’s not the only issue. It is important that we don’t become so focused on equity that we neglect other areas of education. Can we simultaneously raise and level educational attainment? Initiatives that raise the bar may improve attainment for all but won’t necessarily close the gap.

This prompts a further question of individualism versus collectivism; how much do we value diversity and how fair do we want to be? But perhaps that’s the topic for another Goodison debate …..