Education Futures: Who should run Scotland’s schools?

Wednesday 2 February 2022, online

Introduction

Significant environmental, technological and societal change is expected in Scotland in the next two decades. We will have to change how we live our lives to adapt to, and avoid further, climate and ecological change. Technological innovation will create moral dilemmas as it pushes the boundaries of what is possible. And communities will change as our population moves, diversifies and ages.

In this context, Scotland’s Futures Forum hosted a seminar with the Education, Children and Young People Committee on what this change means for our education system and how it can best respond.

Held in conjunction with the Goodison Group in Scotland, the seminar featured contributions from a range of expert perspectives, sharing their views under the Chatham House rule. The debate covered the cultural context of education in Scotland, the roles of learners, teachers, education officials and political representatives, and the challenges for the future.

Attendees

External guests:

Isabelle Boyd is a former teacher, headteacher and senior local authority officer. Having been awarded a CBE in 2008 for her services to education, Isabelle has served on national working groups, including to establish the Scottish College for Educational Leadership.

Graham Donaldson is a former teacher and schools inspector who has played a central part in Scottish educational development. A former head of Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education, Graham is a member of the First Minister’s International Council of Education Advisers, Honorary Professor at the University of Glasgow, and a board member of the Goodison Group in Scotland.

John Edward has been Director of the Scottish Council of Independent Schools since April 2010, representing mainstream and complex ASN schools. In this capacity he sits on a range of national boards and working groups. He is also a trustee of the Scottish European Educational Trust.

Angela Morgan recently chaired the independent review into the provision of additional support for learning in schools, which reported in summer 2020. Angela has wide experience in the third sector, and was awarded an OBE in 2018 for her work with children, young people and families.

David Watt is chair of Fife College and a board member of the Goodison Group in Scotland. Until recently, he was executive director of the Institute of Directors in Scotland, while much of his prior working life was in education.

Members of the Education, Children and Young People Committee:

- Stephen Kerr MSP (Committee Convener)

- Kaukab Stewart MSP (Committee Deputy Convener)

- Stephanie Callaghan MSP (Committee Member)

- Bob Doris MSP (Committee Member)

- James Dornan MSP (Committee Member)

- Fergus Ewing MSP (Committee Member)

- Meghan Gallacher MSP (Committee Substitute Member)

- Ross Greer MSP (Committee Member)

- Michael Marra MSP (Committee Member)

- Willie Rennie MSP (Committee Member)

Officials:

The event was supported by officials from the Futures Forum, the Scottish Parliament and the Goodison Group in Scotland.

Other resources

Visit the Education, Children and Young People Committee webpage

Visit the Scotland’s Futures Forum website

Read about the Goodison Group in Scotland

Read all about the Scotland 2030 Education Project

Read the OECD publication “Trends Shaping Education 2022”

Background: Scotland over the next twenty years

Rob Littlejohn, Head of Business, Scotland’s Futures Forum

Looking to a future that will be marked far more by change than by stability, Rob set out the wider context for the seminar by addressing three key areas of transformation: society, the environment and technology.

Rob indicated that Scotland faces the challenge of an increasingly ageing society, along with more population movement, including the likely depopulation of rural areas. Developments in technology, as well as legislation (e.g. the incorporation of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child), mean that people will be more empowered to take decisions, or at least it may seem that way.

However, society will become more atomised, which, in education, may bring about a greater focus on classroom culture and the role that school buildings play within local communities.

“There may be a greater focus on classroom culture and the role that school buildings play within local communities.”

Our climate is changing, and Rob highlighted that extreme and unexpected weather events will affect education—for example, flooding in schools. He identified two key challenges: how we react and how we prevent further change. He spoke of the pressure on decision-makers to consider sustainability as part of every policy, which would have an impact on education and on communities more broadly.

Finally, Rob noted that technology continues to develop at an incredible pace, and that artificial intelligence will bring both tools to change how we do things and opportunities to do new things, including in schools. However, he also highlighted the moral and ethical issues around AI and the need to balance apparent effectiveness with ethics.

Facing 20 years of change, we need to respond in a positive and flexible way rather than being overwhelmed. Rob pointed out that creativity, empowerment and collaboration are therefore important: we must create new solutions to new problems; empower people by involving them in the decisions that affect them and collaborate by building and renewing partnerships.

Presentation: Who should run Scotland’s schools?

Professor Graham Donaldson, Goodison Group in Scotland

Graham began by indicating that, while the question of who should run Scotland’s schools is deceptively simple, it raises complex issues. Even seeking inspiration from around the world is not straightforward, as countries that are seen as having successful educational systems differ widely in their approaches. For example, Singapore is highly centralised with clear lines of decision-making, whereas Estonia is much more decentralised.

Graham highlighted the importance of cultural context, pointing out that how schools are run depends heavily on culture and tradition. As a result, there is no universal formula for success, but Graham noted that emerging trends and growing pressures should inform our thinking. He argued that making decisions in the educational sphere requires the “intelligence and willingness to anticipate and embrace change, and the agility to translate strategy into action.” He cited the current educational reform programme in Wales, with which he has been closely involved, as an example of positive change.

“How schools are run depends heavily on culture and tradition. There is no universal formula for success.”

As has been widely acknowledged, the pandemic has accelerated and accentuated developing trends and revealed underlying issues. Graham identified two key lessons from the past two years: the potential of technology to enhance learning and teaching, and the vital importance of schools, especially for those from disadvantaged backgrounds. The pandemic also highlighted the limitations of exams and the need to consider different modes of assessment.

Forces such as technology, globalisation and changing social attitudes were already changing aspects of learning. Graham noted that, while countries are now more interdependent, competition is intensifying, and skills requirements are changing. While traditional forms of learning remain important, they are not enough. He argued that educational professionals need to ensure that children have both the capacity for lifelong learning and the ability to apply that learning creatively.

Graham went on to indicate the societal changes that pose challenges to us as individuals, community members and citizens. He noted that beliefs now often override critical thinking, evidence and rational debate, and that our sense of identity is no longer just physical, but virtual. He said that, in this context, “the role of education has never been more important in helping our young people to develop shared and individual values and not to be afraid of complexity.”

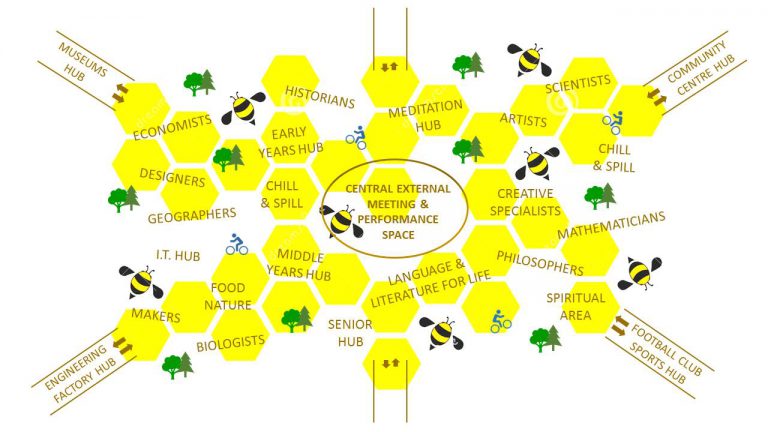

Graham identified some changes that we might see. For example, schools as distinct institutions may change significantly or disappear. He noted that, while schools are currently run by a combination of central and local mechanisms of linear control, the reality is much more complex.

Graham stressed the fundamental question of how what matters in education is determined and pointed out that decision making in education involves a complex interplay of forces, interests and individual decisions and shifting hierarchies in response to a host of competing pressures. He stated that, while Scotland performs quite well internationally, we aspire to do better. He identified that the political debate about education, as with so much else, has become more polarised.

Rather than looking only at questions of power and authority, Graham suggested that we ask how Scotland’s education system can best create the conditions for young people to receive an engaging, challenging and satisfying educational experience to enable them to thrive in a complex and competitive world. He raised a series of questions: who decides what learning looks like, what should be set centrally and what should be determined by schools and teachers? How can we avoid the binary positions that have all too often characterised the educational debate? Are we sufficiently future focused, or are we simply trying to get better at things that are no longer relevant?

“Who decides what learning looks like, what should be set centrally and what should be determined by schools and teachers?”

Over the past 40 years, educational change has largely been driven from the centre, with schools implementing change, but Graham argued that this linear approach is ill-suited to change. Nevertheless, he asserted that we must retain the best of the past while building the future. He highlighted the good points of Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence (CfE), including its innovative focus on capacities, but maintained that its approach has not been fully realised.

Graham underlined the need for agreement on the fundamentals of education, and on what success would look like. He identified that “the prize lies in schools and teachers feeling ownership of educational policy and working to make it a reality.” He also highlighted the roles of young people, parents and carers, employers and wider society, and noted that pupil voices should be heard at every level. He argued that we have to think radically about assessment and accountability, and how we ensure that what counts is also what matters.

Finally, Graham emphasised the need to engage with all key stakeholders, broaden participation in policy making and respect local decision making. We need to invest in professional skills and develop our capacity for resilience and responding to change.

Round-table discussion

Changing the culture: from rhetoric to reality

Graham argued that the answer to who should run Scotland’s schools is “not a redrawn organogram, but a change of culture”, and participants agreed that this was a big challenge. It was stated that the current system is characterised by consensus and conservatism, and that we need to embrace change and new ideas and “move away from the aye-beens.”

However, it was pointed out that, while looking to the future, we need to retain the best of what we have. Participants highlighted the positive aspects of the current system, arguing that parents and children are reasonably happy with how things are. While it was noted that—as Graham said—the CfE capacities have stood the test of time, strong disappointment was expressed that it had become “bogged down in mechanistic approaches.” It was argued that, although Scotland has some excellent legislation and policy on education, “the gap between rhetoric and reality is large.”

Participants stressed that “maintaining traditions is not the same as traditionalism.” Nevertheless, it was argued that the imperative for innovation is crucial, and that professionals and decision makers must be radical in changing the culture. It was suggested that international examples such as Finland, where there is greater trust between teachers and society, might point the way to culture change. However, it was pointed out that we should nevertheless be wary of making international comparisons without taking context into account.

“The imperative for innovation is crucial, and professionals and decision makers must be radical in changing the culture.”

Questions were raised about what we actually mean by changing the culture, and the need to be more precise about that. It was argued that, while we need to situate education policy within a wider strategy and take a broader view, we also need a better understanding of the detail of implementation, while nevertheless giving professionals the autonomy and flexibility they require.

Decentralisation, participation

Flexibility and autonomy were identified as key themes in considering who runs education. It was argued that our education system is currently too bureaucratic and centralised, and that a decluttering of structures and systems is required. It was noted that, while it may seem counterintuitive, “We need a system and a culture that is less complex to help us deal with complexity.”

Participants stressed the need for autonomy in governance, curriculum and learning, and it was argued that bodies must be able to operate as nimbly as possible to respond to challenges and change. It was reiterated that Government needs to let professionals get on and do their job, with teachers sometimes thinking, “Gonnae leave us alone for five minutes!”

It was suggested that any culture change around how we run schools must involve developing a notion of society in which professionals are given more trust and respect, as in Scandinavian countries. Participants highlighted issues with interference by politicians, and it was asserted that we need to be clearer about the role of the centre and what part the Parliament and Government should play in setting a strategic direction.

“We need to be clearer about the role of the centre and what part the Parliament and Government should play in setting a strategic direction.”

It was suggested that the current bureaucratic culture is excluding people, and that too much jargon meant that education policy in Scotland “can be cluttered and verbose.” In arguing for greater participation at all levels of decision making, the system needs to create space to listen to local communities, children and young people and those who are closest to implementation. However, an important question was raised: once we have listened to those views, what do we do with them? It was emphasised that people participate not simply to be heard, but in order to be able to direct policy that suits their community.

Participants disagreed over the extent to which education policy should be nationally prescribed. It was argued that such an approach does not work in a school system, and that instead we need clarity about national purpose and what matters, along with buy-in. However, it was highlighted that leaving education policy to local discretion leads to both great practice and bad practice, so national prescription may therefore be necessary. It was suggested that, if we are to have true flexibility at a local level, we need a political consensus on the approach to avoid political sloganeering around ‘postcode lotteries.

In negotiating decentralisation and culture change, the importance of trust and relationships was emphasised. It was mentioned that we need to invest in leaders, as skills around communications and trust are critical to success. The importance of accountability for professionals alongside greater responsibility was highlighted. Once again, participants spoke of the importance of buy-in, so that professionals embrace changes rather than seeing them as a bureaucratic burden.

Conformity or creativity?

As Graham flagged up in his presentation, a key element of deciding who runs our schools involves tackling the broader question of what we value and what education is actually for. A related question concerns what we want to focus on and what we should measure. Going back to the overarching theme of culture change, it was argued that we cannot change the educational culture if we, as a country and a society, cannot decide what kind of citizens we want.

It was suggested that, while we may say that education in Scotland is about creativity, it is still essentially about conformity. Participants discussed what we measure in schools, how we assess progress and the important link between what we value and what we measure. It was asserted that there is too much focus on statistics, and that we need to explore ways of capturing and measuring what we value at all levels. Do we spend too much time and resource on measuring things that do not matter? It was argued that “politicians are always looking for the wrong thing”, and that, even if the right data is gathered in schools, politicians tend to use it simply to attack or defend Government policy.

It was noted that such an approach had led to an over-reliance on exams. As one participant asked, “Why do we torture kids in exams? It doesn’t even give us good results.” The importance of language was highlighted—it was pointed out that when we talk about learning, we mean attainment, by which we mean passing exams. Conversely, it was asserted that Scotland is doing some things well that are not being measured. It was suggested that the overall picture in education is “not all doom and gloom”, and that CfE has been a huge success in making young people more confident and well-rounded.

Nonetheless, it was stated that placing too much importance on assessment has led to a system that is not focused on children. Participants emphasised that we need to see and deal with children as they are, rather than viewing them as identical units that process information. In particular, it was seen that this approach disadvantages children with additional support needs and also leads to a lack of parity of esteem for vocational education.

“Placing too much importance on assessment has led to a system that is not focused on children.”

The point was made that improving our approach to education for children with ASN would be a good base for making wider educational policy. It was noted that 30.9 per cent of children and young people in Scotland are defined as having an additional support need, and that we should put this group at the core of our education system as we develop a vision for the future, because “if you get it right for them, you’ll get it right for all children.”

Skills for the future

Linking in with the theme of inclusivity, participants discussed the potential of the digital world to enhance the whole process of learning and create radical change in the education system. It was asserted that, while traditional forms of learning remain important, they are not enough. Participants noted that we often do not teach children the skills to use technology properly, and that, in embracing digital, we need to involve the big players in the technology industry.

However, the importance of a hybrid approach, and of not losing sight of the vital human element in education, was emphasised. It was pointed out that, through the pandemic, we learned that teachers are essential as “the humans that little humans want to interact with” and we need to value them as such. The firm view was expressed that while digital devices enhance learning, they do not replace it. Linking in with the theme of decentralisation, a clear emphasis was placed on the importance of school ethos and identity within a local community. It was indicated that that is particularly true for those in deprived areas, and that we need to ensure that we do not see “the baby thrown out with the bathwater in the digital age.”

“Teachers are essential as they are the humans that little humans want to interact with.”

Technology can provide alternative pathways to support learning, but—returning to the need for a broader view—participants stressed that we need joined-up policy to avoid issues such as digital poverty posing problems and leaving children behind. Participants also highlighted the necessity of developing non-digital skills and ways of gathering knowledge. It was suggested that input from the broader world of work is essential in ensuring that young people are more aware of opportunities post-school. In addition, a focus on debating and critical thinking skills was identified as a crucial element of the future education landscape.

Re-energising the debate

As Rob emphasised, schools are a central point where all these questions and challenges come together. It was stated, in the context of arguments for greater participation and broader input, that there have already been plenty of opportunities—especially following the pandemic—to identify and consider divergent views and approaches. The crucial question is, to what extent are we prepared to take those views on board? It was noted that “unity in view is not something we are ever going to get.”

It was underlined that, while CfE is certainly not a failure, it is work in progress and it needs re-energised. There was a general consensus that, as we move forward in addressing the question of who runs our schools, it is essential to recreate the excitement and creativity that led to the development of CFE. We need a joined-up approach, developing the direction of education within a wider strategy that involves schools and communities, professionals and parents, and—importantly—young people themselves. That requires flexibility and autonomy, and a clear view of what we value.

“We need to develop the direction of education within a wider strategy that involves schools and communities, professionals and parents, and—importantly—young people themselves.”

As was pointed out, education is about fitting people for both life and work. By considering all these questions, we can—as Graham said—begin to “build a better future, rather than a better past” for all Scotland’s young people.

Partners