Education Futures: Classrooms of the Future

Wednesday 16 March 2022, the Scottish Parliament and online

Introduction

Significant environmental, technological and societal change is expected in Scotland in the next two decades. We will have to change how we live our lives to adapt to, and avoid, further climate and ecological change. Technological innovation will create moral dilemmas as it pushes the boundaries of what is possible. And communities will change as our population moves, diversifies and ages.?

In this context, Scotland’s Futures Forum hosted a seminar with the Scottish Parliament’s Education, Children and Young People Committee on how the learning experience in schools will, and should, continue to change alongside developments in society and technology.

Held in conjunction with the Goodison Group in Scotland, the seminar featured contributions from a range of experts, covering several perspectives. Views were shared under the Chatham House rule.

Participants considered the daily experience of school life and, more broadly, the implications of major societal challenges, such as the climate and nature crises and the recent Covid-19 pandemic, for what and how we teach. In this context, they also considered our expectations of children and young people as they learn their way towards a sustainable future.

Attendees

External guests

Professor Peter Higgins holds a Personal Chair in Outdoor Environmental and Sustainability Education at the University of Edinburgh. A former teacher of biology and outdoor education, Peter is internationally recognised for his work and is director of Scotland’s UN accredited centre for Education for Sustainable Development. He has served on a number of national and international policy advisory groups.

Lydia Everitt is one of three directors of Braw Talent, a Glasgow-based social enterprise committed to making creative career pathways more accessible to young people. A qualified secondary teacher of art and design, Lydia is a Glasgow School of Art graduate who has exhibited in galleries such as the Royal Scottish Academy, and her work forms part of the Scottish National Collection.

Greg McDowall has been headteacher in West Lothian for the past four years and joined West Calder High School in January 2020. Under Greg’s leadership, the school underwent a digital transformation during the Covid-19 pandemic and is developing the school curriculum to include a range of interdisciplinary work-based experiences for young people.

Professor Judy Robertson is Chair of Digital Learning at Moray House School of Education at the University of Edinburgh. A computer scientist and learning technologist, she has expertise in designing technology with, and for, children, and evaluating educational technology in classroom settings. During the Covid pandemic, Judy ran professional learning seminars with teachers on supporting digital and online learning.

Graham Donaldson is a former teacher and schools inspector who has played a central part in Scottish educational development. A former head of Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Education, Graham is a member of the First Minister’s International Council of Education Advisers and Honorary Professor at the University of Glasgow. He also has extensive international experience, including as an expert adviser for the OECD. Graham is also a board member of the Goodison Group in Scotland.

Members of the Education, Children and Young People Committee

- Stephen Kerr MSP (Committee Convener)

- Kaukab Stewart MSP (Committee Deputy Convener)

- Stephanie Callaghan MSP (Committee Member)

- Graeme Dey MSP (Committee Substitute Member)

- Bob Doris MSP (Committee Member)

- Fergus Ewing MSP (Committee Member)

- Ross Greer MSP (Committee Member)

- Michael Marra MSP (Committee Member)

- Willie Rennie MSP (Committee Member

Officials

The event was supported by officials from the Futures Forum, the Scottish Parliament and the Goodison Group in Scotland. It was chaired by Rob Littlejohn, head of business at Scotland’s Futures Forum.

Other resources

- Visit the Education, Children and Young People Committee webpage

- Read about the Goodison Group in Scotland

- Read the independent report “Putting Learners at the Centre” by Ken Muir

- Read the UN Environment Programme report “Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, the Working Group II contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report

- Read about the OECD work “Trends Shaping Education 2022”

Presentation: Classrooms of the future

Professor Peter Higgins, University of Edinburgh

Peter began by stating that, despite the seminar’s title, he would focus on the school, rather than the classroom, of the future, for reasons that would become clear. He cited his favourite educational parable, Harold Benjamin’s classic work The Saber-Tooth Curriculum, which contends that, while children living in the Stone Age were taught key skills for survival, their curriculum had to change radically when the Ice Age came.

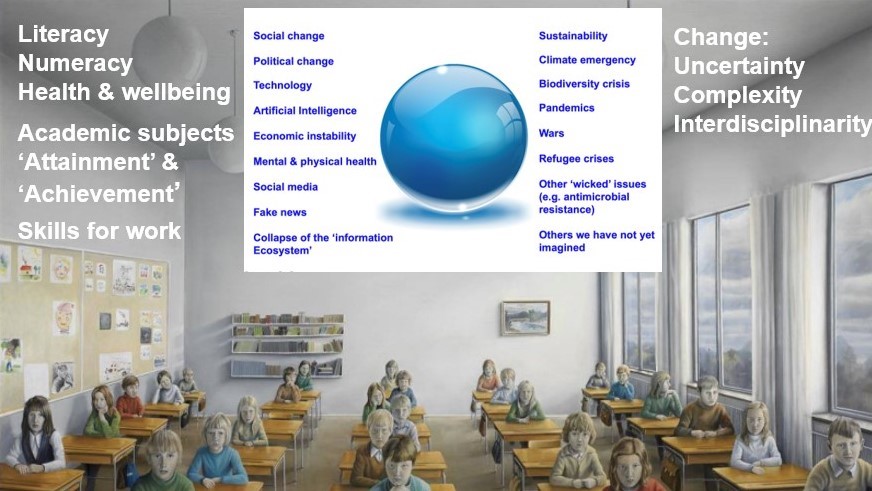

In short, our education system has to adapt as society moves on, and we must think about what skills our young people might need as they navigate a fast-changing world. Peter argued that, while we cannot predict the future, we need to think broadly about what our future might look like and how big issues such as the climate and biodiversity crises are likely to manifest themselves.

In that context, Peter outlined the wider picture, noting the “scary” conclusions of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports, and highlighting Scotland’s strong policy commitments to reducing carbon emissions. He argued that we need to bear in mind the idea that nature and climate are intimately and inextricably linked, and cited David Attenborough’s view that the only way out is to “rewild the world”.

Referring to the Stockholm Resilience Centre’s concept of the nine planetary boundaries within which humanity can survive and thrive, Peter explained that, given the ways in which our physical processes are affecting the planet, we are exceeding our safe operating space. If we continue to go beyond these limits, we face runaway climate change and other irreversible impacts (see IPCC 6th Assessment – February 2022).

When does the future start?

As Peter pointed out, evidence shows that the impacts of climate change and biodiversity loss will dwarf the impacts of Covid if we do not start to make positive changes. He asserted, however, that finding solutions to “wicked problems”, which involve complex interdependencies, can be very hard. We have to start by understanding that the world is a complex place, and that the education and skills young people need will change. Peter highlighted the profound importance of education in changing the lives of his own parents and grandparents, and he stressed the need for a holistic view that encompasses the entire age range of learners in Scotland’s schools.

When does the future start? Peter argued that the publication of Ken Muir’s report “Putting Learners at the Centre”, which sets out a future vision for Scottish education, along with the incredibly powerful imperative of the climate crisis, prompts us to start thinking right now about how we change education. As Peter noted, a child born since the year 2000 is likely to live for 100 years. What are they going to see in their lifetime, and how do we prepare them for that? Peter argued that schools face constant change and uncertainty, and that complex structures make it difficult for them to take an interdisciplinary approach.

Peter raised a question: why do we still need knowledge when it is available at the touch of a button? He pointed out that, while schools are very good at teaching basic skills, young people need a deeper understanding, and the ability to extract meaning from information, to enable them to understand reality and interpret the world.

As he emphasised, interdisciplinary learning is essential in that regard. Peter argued that exams are useful for assessing knowledge, but not much else, and reiterated the need for young people to develop more complex skills. He noted that universities, through their selection criteria, currently drive the education system, and that approach needs to be questioned.

Complexity, uncertainty and change

Citing philosopher John Dewey’s view that education is not a preparation for life, but life itself, Peter stressed that the education systems of the world will nevertheless have to adapt to prepare us to deal with complexity, uncertainty and change. Learners will need critical awareness and the capacity to continue to learn. That raises a question: what should be at the core of our knowledge, and what does that mean for education?

Peter argued that it is essential that we see ourselves as part of, rather than apart from, the environment, and that we educate young people to develop respect for themselves and others, for future generations, (of all species as well as ours), and for the environment—which provides us with the “ecosystems services” without which we would not survive.

As Peter stressed, it is profoundly important for young people to be confident and critique everything; to learn how to deal with complexity and change; and to do so with realism and optimism. We also need to think about how young people can contribute positively to their own development. As he said, it would be great if all our young people left school thinking, “I want to pass on a lasting positive legacy to future generations.”

Peter went on to emphasise connection and the need to understand the consequences of our actions, leading to an ethic of care and citizenship. He described how the UNESCO four pillars of education—learning to know, to do, to be and to live together—can create a context for that.

Powerful educational benefits

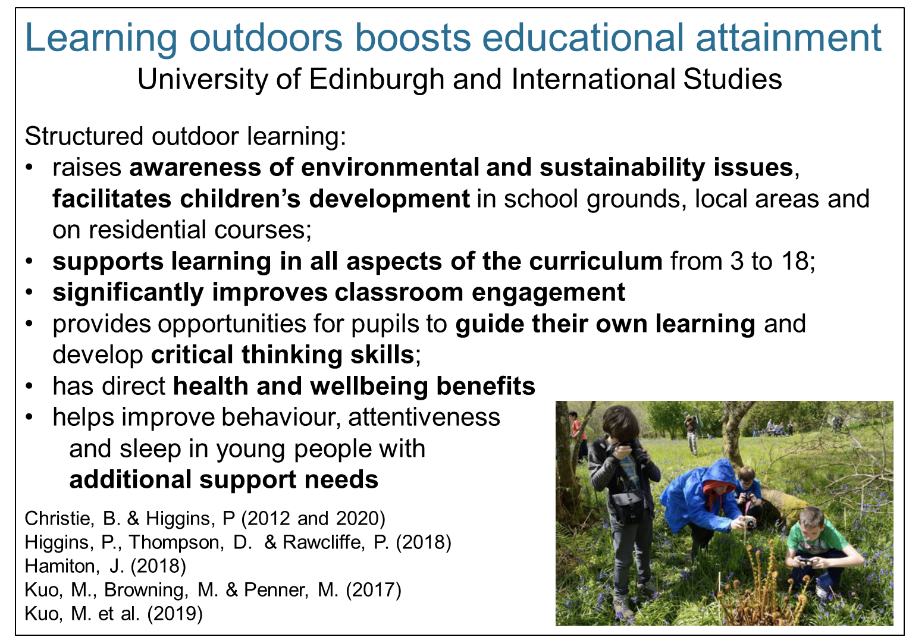

What does “learning for sustainability” mean? Describing it as a dynamic, engaged process, Peter emphasised that it is about values and attitudes, knowledge and skills and the confidence to take decisions. It brings together education for sustainable development, global citizenship and outdoor learning, and he noted that it already has support among Government ministers in Scotland.

However, the introduction of the concept of ‘Learning for Sustainability’ has been patchy across Scottish schools, and there is an issue with how we ensure consistency in respect of positive engagement with policy.

Peter highlighted the positive educational outcomes that are associated with learning for sustainability—noting, for example, that research shows that outdoor learning has powerful educational benefits for all curriculum areas. He stressed the importance of children developing a connection to nature and benefiting in terms of health and wellbeing—especially given that, during the pandemic, opportunities to spend much time outdoors were limited for many.

Peter emphasised that we need to consider how we place learners at the centre of the school and the school at the centre of the community, but questioned what that might mean. Schools are a community in themselves, but they have to link in with broader community aspects too. He stressed the need to place the learner at the centre of our decision making, and the importance of considering the principles that we apply in developing the future of Scottish education.

“The current generation of learners see climate change as one of the most significant issues they face”

Peter highlighted the first two core principles in Ken Muir’s report: that our work must be directed by the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, and that we must recognise that the current generation of learners see climate change as one of the most significant issues they face.

Nevertheless, Peter stressed that climate change is a catch-all term for a whole range of inter-related sustainability issues, and he reiterated the interlinked nature of the changes required in response. He argued that, on a broader scale, we must link with the planet as a system, finding our place within it as societal members and engaging in that process as a nation.

In conclusion, Peter highlighted the recent climate protests by young people as a great example of a learning environment. He noted, however, that we must not assume that future generations are going to solve the issues of today, and that our work in education must align with that view.

Round-table discussion

In responding to the themes highlighted in Peter’s presentation, participants discussed key concepts such as empowerment, trust, sustainability, critical thinking and creativity as well as an interdisciplinary approach.

The discussion not only highlighted specific issues relating to various stages of the education system in Scotland but encompassed wider questions—picking up on key ideas that Peter outlined—about the role of schools in the community, what education is for and what needs to change.

Participants also considered the context for change: where we are now, taking the tentative first steps from pandemic to recovery, the current state of education and the opportunities offered by Ken Muir’s report.

A lack of focus on excellence?

Participants considered the profoundly important question of what education is for, noting that there are a range of possible answers, such as individual development, attainment and meeting our economy’s needs. It was pointed out that we need to consider not only society’s needs, but what young people themselves want. It was reiterated that, as Ken Muir’s report highlights, one in three young people feel that their education is not meeting their needs, which is leaving them disenfranchised.

In the context of Peter’s focus on learning for sustainability, participants stressed the importance of knowledge and problem-solving skills as part of the learning process. However, it was asserted that we should focus on our goals as a society, rather than on specific skills that might be needed in the future, especially given that—as was pointed out—trying to predict technological change is “always a fool’s game.”

“The current system focuses too much on what can be reliably assessed, rather than on things that really matter.”

Participants highlighted the central role of creativity in education and questioned whether schools are too conformist and try to make square pegs fit in round holes. It was argued that young people must develop the cognitive and emotional skills to enable them to deal with the future possibilities that Peter outlined. Communication skills and tools were highlighted as key, especially in the context of giving young people a voice. It was argued that we should be “empowering young people to share and use their own voice and equipping them with the skills to do that.”

Concerns were expressed that knowledge is not valued enough in the education system. There were worries about “a lack of focus on excellence”, with participants arguing that we need to be “lifting people to the very top of their capacity” if we want education to play a role in developing solutions to climate change issues. It was countered that, although knowledge matters, “being able to use knowledge matters even more”, and it was suggested that such skills are not currently encouraged. Participants noted that the current system focuses too much on what can be reliably assessed, rather than on things that really matter.

Challenging the status quo?

In the light of differing notions of what education is for, participants considered how, in a practical sense, we should go about educating young people for the world that lies ahead. There was enthusiasm for putting an interdisciplinary learning approach at the heart of teaching, which should—as Peter identified—include learning outside the classroom.

A crucial aim was articulated: we need to “give young people a learning experience across different disciplines.” Reiterating the point about taking account of what young people want, participants emphasised the need for pupil-led approaches and making space for young people’s voices to be heard. It was asserted that the education process must ensure that young people are “engaged and involved with creating their own learning environments.”

Participants identified critical thinking as a key skill for the future, although there were differing views on what that might mean. It was argued that “we cannot criticise people and other points of view all day”, and that data-driven problem solving was more important if we want education to help solve environmental issues. However, it was emphasised that critical thinking is about looking at an issue from both sides and finding worth in an opponent’s arguments. It was asserted that critical thinking is about curiosity and rigour, and “not about criticising but challenging the status quo.” Participants argued that critical thinking is an essential skill, as we need to identify the types of problems that Peter described in order to solve them.

Returning to Peter’s point about the role of schools in the community, participants questioned what that should mean in practical terms. The recurring theme of where education should sit within society was raised, and it was noted that there were examples across Scotland of young people undertaking work in their communities, especially on environmental projects.

A problem with trusting our teachers?

Discussing practical changes that might be required, participants talked about the need for decluttering, but there was a mix of views on what that might mean. It was argued that the curriculum, in particular at primary level, is too cluttered, but participants also stressed the need for a streamlining of structures, given that there are “so many layers of accountability in education.” It was noted that clarity around responsibilities was important, and that while certain activities are best undertaken by local authorities, “schools are at the heart of the community.”

Participants raised the familiar theme of micro-management and asked whether we have “a problem with trusting our teachers.” Issues of trust were also highlighted with regard to young people; participants argued that it was essential that learners are able to trust school leaders to give them the best opportunities possible.

In addressing issues of structure and governance, it was asserted that, regardless of the specific bodies that are set up, the important point is “what we are trying to do and how we create a context in which that becomes reality.” Participants went on to discuss, therefore, whether there is an implementation gap when it comes to education policy. There was a focus on practicalities, and participants emphasised the need to “translate all this into a living reality for learners in our school system.”

Participants raised the familiar theme of micro-management and asked whether we have a problem with trusting our teachers.

To that end, it was argued that we need teachers to be educators, rather than trainers. It was emphasised, however, that “schools have done a tremendous job” in implementing the four capacities, for example, and that the real problem was a lack of consensus and clarity at a political level, which meant that “when educationalists are asked to deliver on the ground, it all just breaks apart.” Participants stressed that politicians have a responsibility to understand the impact of changes in practical terms.

A different interpretation was offered—we may have a realisation gap regarding our aspirations, and an opportunity gap in respect of ensuring that “the opportunities offered by curriculum for excellence are actually realised in practice for our young people.” It was argued that, overall, the main issue was that, when it comes to education in Scotland, “we’ve lost the sense of purpose.”

A total disaster or a bounce-back effect?

In thinking about the future of education, participants considered where things currently stand. The pandemic experience of the past two years has brought many changes to education in Scotland and around the world, but there were differing views—and robust discussion—on whether those changes were largely positive or negative.

Participants discussed the virtual and hybrid learning models necessitated by the pandemic, and whether the adoption of such technology was a preview of changes to come. It was argued that there was “evidence of new skills that teachers and learners have picked up digitally” during the pandemic, and that improvements in that regard would “lead to improved outcomes for young people.”

It was asserted that, while there was definitely room for improvement, there was also cause for optimism given how teachers and young people had responded to the challenges.

Deep concern was expressed about “the number of people who have been disengaged” by the pandemic experience of education. It was argued that, while there were anecdotal references to benefits, the little data available showed that education during the pandemic “has been a total disaster” and that “attainment is at its lowest in a generation.”

“The response of the education system to the Covid-19 pandemic is crucial in reshaping the future”

Nonetheless, it was countered that, while there may have been “an immediate dip” in attainment during lockdown, “there has been a bounce-back.” It was also noted that secondary schools in Scotland had recently achieved “record levels of positive destinations.”

It was suggested that good things are happening, but we may not be capturing them. Participants agreed that evidence was essential, but there were contrasting views on whether the evidence was already there. It was argued that there were no data on the pandemic experience “other than some positive words.” Nonetheless, participants asserted that, whatever the realities of that experience, it is what we do now that counts, and that the response of the education system is crucial in “reshaping the future.”

An exciting opportunity for change?

Participants highlighted the differing experiences at different levels of education and stressed that the various strands could learn from one another. The importance of partnerships and collaboration was emphasised, but it was pointed out that schools need to have “time for teachers to collaborate effectively.”

It was argued that, while “changing the way we work within schools” is important, and we need to look again at specific elements of the system, such as the senior phase, we must also recognise that “pupils still only have so many hours in the day, and school is not the only part of their life.”

It was asserted that, in order to tackle the issues that Peter highlighted, a truly radical approach would be required, and that “we have to talk about how we contribute to those big issues in a big way.”

Despite differing views, and some scepticism about the ability to deliver truly radical change that would meet the requirements that Peter outlined, participants expressed the view that, overall, “we’re on the cusp of a really exciting opportunity for change”.

Partners