Enlightenment Scotland: a “civilised nation”?

By Nicola Martin, @NicolaMartin14

“We look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilisation.”

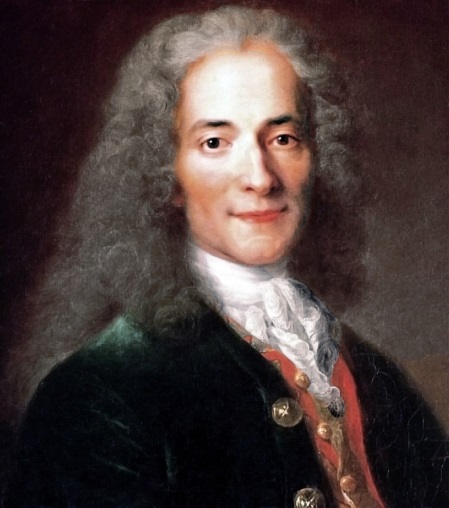

This summary of a quotation from French Enlightenment philosopher Voltaire is commonly used by commentators who wish to present Scotland as a beacon of civilisation and enlightenment in both the past and the present. [1] However, such a phrase and interpretation is problematic. It provides little analysis of the true historical picture and instead contributes to the myth of Scottish exceptionalism that has suggested that 18th-century Scotland was somehow morally and intellectually superior to the rest of the world: a myth encapsulated in Arthur Herman’s Scottish Enlightenment: The Scots’ Invention of the Modern World.

Utilising such a short phrase in order to argue that Scotland represented the epitome of what it was to be civilised in that age also fails to take into account the vast differences within Scotland, instead suggesting a national homogeny that simply did not exist.

To consider exactly what Voltaire meant in a more useful manner, it is worth revisiting the concept of civilisation itself, which I noted in a previous post emerged during the Enlightenment in the context of being in opposition to barbarity as a state of being for an individual, group, or nation.

The idea of progress, which emerged during the Enlightenment, was crucial to the theories of civilisation that developed in that period. Rejecting the cyclical interpretations of history, the theory of progress set forward an interpretation based on the linear movement of society from the primitive, savage past to the civilised future. [2] Adam Ferguson argued that civilisation was the final stage a society could reach in its progression, famously stating: “Not only the individual advances from infancy to manhood, but the species itself from rudeness to civilization.” [3]

Theories of progress suggested that advances in technology, science and social organisation could lead to improvement in the human condition and, therefore, that an uncivilised society had the opportunity to progress and become civilised. The theory of progress that emerged during the Enlightenment was an optimistic interpretation in that it emphasised the actuality rather than simply the theoretical possibility of improvement. The theories which emerged clearly suggested that to be civilised was the optimum condition for all mankind. The theories were also inherently hierarchical in nature, suggesting that only those who were already civilized could possibly know what it was to be civilised. [4]

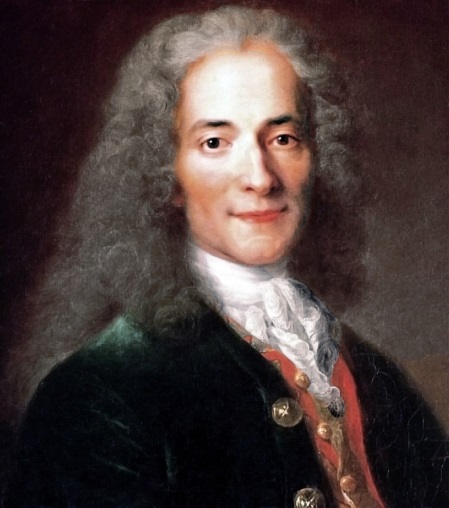

In the mid-18th century, Enlightenment thinkers in Scotland and France, independently of one another, established a stadial theory of the development of man. Stadial theory argued that all societies passed through set stages of development, normally either three or four, in their progression from savagery to civilisation. These studies co-opted the theory of progress to create the paradigm of civilisation that we continue to recognise today, though few would agree with the specifics of the theory itself. For Adam Smith and many of the Scottish Enlightenment theorists, the final, civilised stage that a society could reach was that of a commercial society.

Stadial development was a conceptual framework of human society as an overall entity which was then utilized by those who wished to study specific nations through the lens of history, anthropology or sociology. Such studies made comparisons between nations or societies and explained which stage a particular nation had reached: i.e. whether a nation was civilised or not. As the ideal of civilisation was set down by those who classified themselves as civilised, it is hardly surprising that these studies generally agreed that European, commercial society was the pinnacle of human achievement. Scotland, therefore, was argued to be representative of the fourth, civilised, stage of societal development. But how true was such an interpretation?

Leaving aside the question of whether the Enlightenment definition of what it meant to be civilised was true or not, Scotland was not one homogenous nation in the 18th century. The divide between the Highlands and Lowlands was particularly marked. Whilst Lowland Scotland, and particularly the larger towns and cities, more closely represented industrial and commercial centres found elsewhere in Britain and Europe, in the Scottish Highlands agriculture and subsistence living remained the majority lifestyle for much of the 18th century. A split between the new, rapidly emerging and increasing urban centres and the older agricultural communities was common throughout Britain and Europe but in few areas was the divide as pronounced as that between the Highlands and Lowlands in Scotland. Indeed, many in the Lowlands thought of themselves as more alike to their neighbours further south than those above the ‘Highland line’.

This led to the common view throughout Scotland and Britain that Scottish Highlanders were significantly different from their Lowland neighbour: an uncivilized population group stuck in the earlier stages of development. In his history of Scotland, William Robertson wrote that, in the Highlands and Islands, “society still appears in its rudest and most imperfect form.” [5]

Such a view was not unique to the Enlightenment period; indeed, Highlanders had been viewed as barbaric for centuries and the state had repeatedly attempted to civilize them. The failed Jacobite Uprising of 1745-46 (during which the majority of Jacobite support had come from the Highlands) provided a further opportunity for attempts to be made to civilise that population group, focusing on improving agriculture and introducing commerce in line with the theories of stadial development.

According to the standards of the day, therefore, the Scottish Highlands were specifically left out of any classification of the nation as being civilized and advanced: such a classification referred specifically to the emerging urban centres of the Lowlands. Further than this, contemporary Enlightenment figures in North America including Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin commented specifically on the intellectual genius of Edinburgh, not of Scotland, suggesting that their celebration of Scotland did not assert something unique and superior about the country as a whole.

And, coming back to Voltaire, his comments about Scotland were specifically directed towards the Enlightenment culture and theories that were emerging from what was, in his eyes, an unexpected source. Understood in this light, the oft-quoted “we look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilisation” is simply a celebration of the theories and perspectives emerging from the intellectuals driving of the Scottish Enlightenment, not a judgement on the morality and superiority of the ‘Scottish nation’. And within Scotland itself, the emergence of stadial theory at a time when active civilisation of the Highlands was ongoing and when commentators made a clear distinction between population groups within Scotland and their levels of civility questions the extent to which Scotland as a whole can be argued to have been a civilised nation during the Enlightenment.

Indeed, the fact that Highland society was classified as being uncivilized simply because it did not mirror Lowland society emphasises perhaps the most troubling aspects of the theories of civilization that emerged during the Enlightenment: the hierarchy inherent within such perspectives and the identification of what it was to be civilised in opposition to the ‘other’.

Images

Portrait of Voltaire:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Atelier_de_Nicolas_de_Largilli%C3%A8re,_portrait_de_Voltaire,_d%C3%A9tail_(mus%C3%A9e_Carnavalet)_-002.jpg

Portrait of Adam Smith: https://id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adam_Smith

References

[1] OxfordWords blog, in conjunction with Nicholas Cronk of the Voltaire Foundation, established that “We look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilisation” is an accurate summary of Voltaire’s own words. http://blog.oxforddictionaries.com/2014/09/borrowed-words-editing-oxford-dictionary-quotations/

[2] For more on the theory of progress, see: Jackson, C. ‘Progress and Optimism’ in M. Fitzpatrick et. al. (ed.), The Enlightenment World (London: 2004)

[3] Ferguson, A., An Essay on the History of Civil Society (Edinburgh: 1767)

[4] See various works by Anthony Pagden for more: Pagden, A.. ‘The “defence of civilization” in eighteenth-century social theory’, in History of the Human Sciences 1/1 (1988) pp.33-45, Pagden, A. (ed.), The Languages of Political Theory in Early-Modern Europe (Cambridge: 1987)

[5] Meek, R. L., Social Science and the Ignoble Savage (Cambridge: 1976)

Scotland’s Futures Forum exists to encourage debate. The views expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the Forum’s views.