What might a Scottish welfare system look like in 2020?

On 7 September 2009, in partnership with Skills Development Scotland and the Scottish Government, Scotland’s Futures Forum hosted a seminar with Professor Joakim Palme, Director of the Institute for Futures Studies at Stockholm University. The seminar posed the question ‘What might a Scottish welfare system look like in 2020?’

The seminar was attended by 55 policy makers, academics, researchers and local authority officials with an interest in social policy. Following Professor Palme’s presentation, delegates broke up into groups to consider what lessons Scotland could learn from the Swedish welfare model and how this learning could be put into practice by 2020.

Key Learning Points for a Scottish Welfare System

The Swedish Welfare System

To seed the discussion, Professor Joakim Palme explored the Swedish welfare system and challenged the group to consider what could work in a Scottish context.

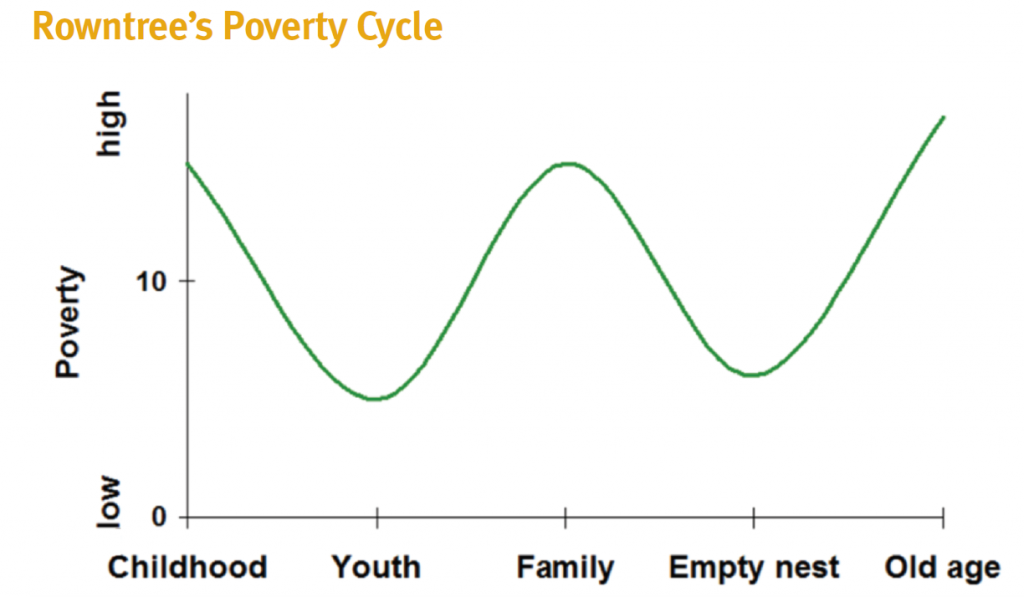

Palme talked about social security, overall, as a response to the inefficiencies of the capitalist system, citing the Rowntree cycle of poverty.

History

The Swedish welfare system was largely developed after the Great Depression of the 1930s, during a period of declining fertility and when agriculture and industry were equally important elements of the Swedish economy.

Characteristics

The welfare system is characterised by

- Universalism in the provision of many benefits

- With some targeting of benefits to the poorest

- Earnings-related social insurance

- Individual social rights

- The dual earner model, which supports women in the workplace

- A social services system that is universal, decentralised and separate from cash benefits

This is funded by a mix of local and centralised taxes as well as employer and employee contributions.

Criticisms

The system is not without its critics, and Palme acknowledged that there is no miracle approach. A 2006 report by the McKinsey Global Institute studied Sweden’s labour market and found that the rate of employment amongst working age adults had declined in the previous ten years, with youth unemployment amongst the highest in Europe.

The McKinsey report put the ‘true’ unemployment rate at 15-17%. In 1970, Sweden was the fourth richest member of the OECD countries, but dropped to the 16th in 1998. Today 10% of the Swedish population is foreign-born and Sweden’s immigrant population are disproportionately affected by unemployment and deprivation.

Challenges

Professor Palme set out what he believed were the main challenges facing the Swedish economy and welfare system, namely globalisation and its consequences for increased mobility of tax bases and an ageing population, which puts increased pressure on intergenerational redistribution. Given that social security is strongly redistributive over the life cycle, he highlighted the tough fiscal pressures on public spending produced by an ageing population.

Professor Palme feels that the debate has been overly focused on pension reforms and savings and that it is important for governments to think carefully about securing their future tax bases. Understanding how social policy interacts with fertility, education and labour supply is also vital.

Discussion

Delegates were asked to consider their aspirations for Scotland from four different perspectives:

- skills and education,

- health and wellbeing,

- the impact of an ageing population and

- political leadership.

They were also asked to specify what powers Scotland would need to create the welfare system of their aspirations.

Skills and education

Delegates thought that the welfare state should be seen as a positive aspect for business and not just a ‘cost’, thereby making Scotland a more desirable place to live and work. We should have a goal of high quality, universal childcare. This would also have the effect of incentivising paid employment for mothers who wished to return to work.

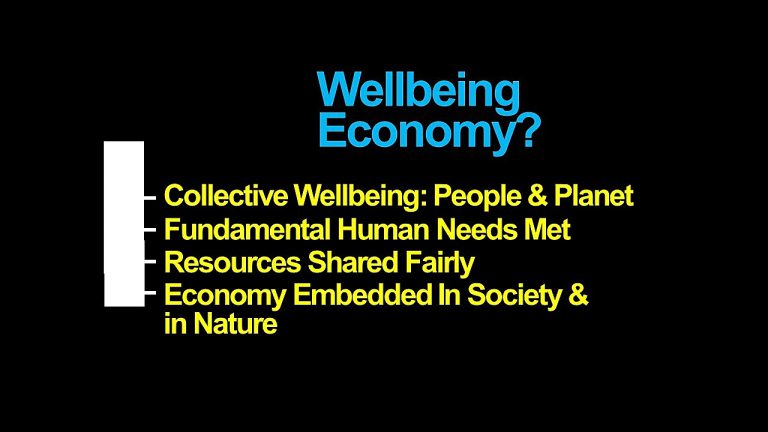

Health and wellbeing

Delegates felt that non-perfect health should not be a barrier to employment and bemoaned the fact that health and wellbeing is not currently seen as a serious political issue. Delegates wished to see workplaces that are more supportive of people with health issues than is currently the case, particularly in mental ill-health. Delegates stressed the importance of early intervention (particularly in the 0-5 year age group) with proper care support packages.

Political Leadership

Delegates also thought that we need to ask ourselves whether the current system is capable of adapting or whether we need to replace it with something else – and if so, how? Policy-making is often incremental, and it is easy to lose sight of the long-term goal. Despite the introduction of the minimum wage, child tax credits etc., there is still substantial inequality. Delegates posed the question: if we want a more redistributive tax system, who is going to pay?

Ageing Population

Delegates were clear that individuals should be able to work as long as they want and that there should be more explicit recognition of caring responsibilities of older people. They were keen to see consideration given to the idea of a carer’s wage.

They felt that Scotland must attract young, productive, economic migrants, able to counterbalance the effects of an ageing population. In order to achieve these goals, delegates were of the opinion that Scotland should have powers over immigration and social security system.

A note on the event

Scotland’s Futures Forum and the Scottish Poverty Information Unit are grateful to the following for leading the discussions:

- Pennie Taylor, Journalist, Broadcaster & NHS Communications Specialist

- Professor J Palme, Director of the Institute for Futures Studies

The organizers are also very grateful to the delegates who attended the day. While not everyone will agree with the conclusions discussed above, this outline and the full event report were based on their deliberations.